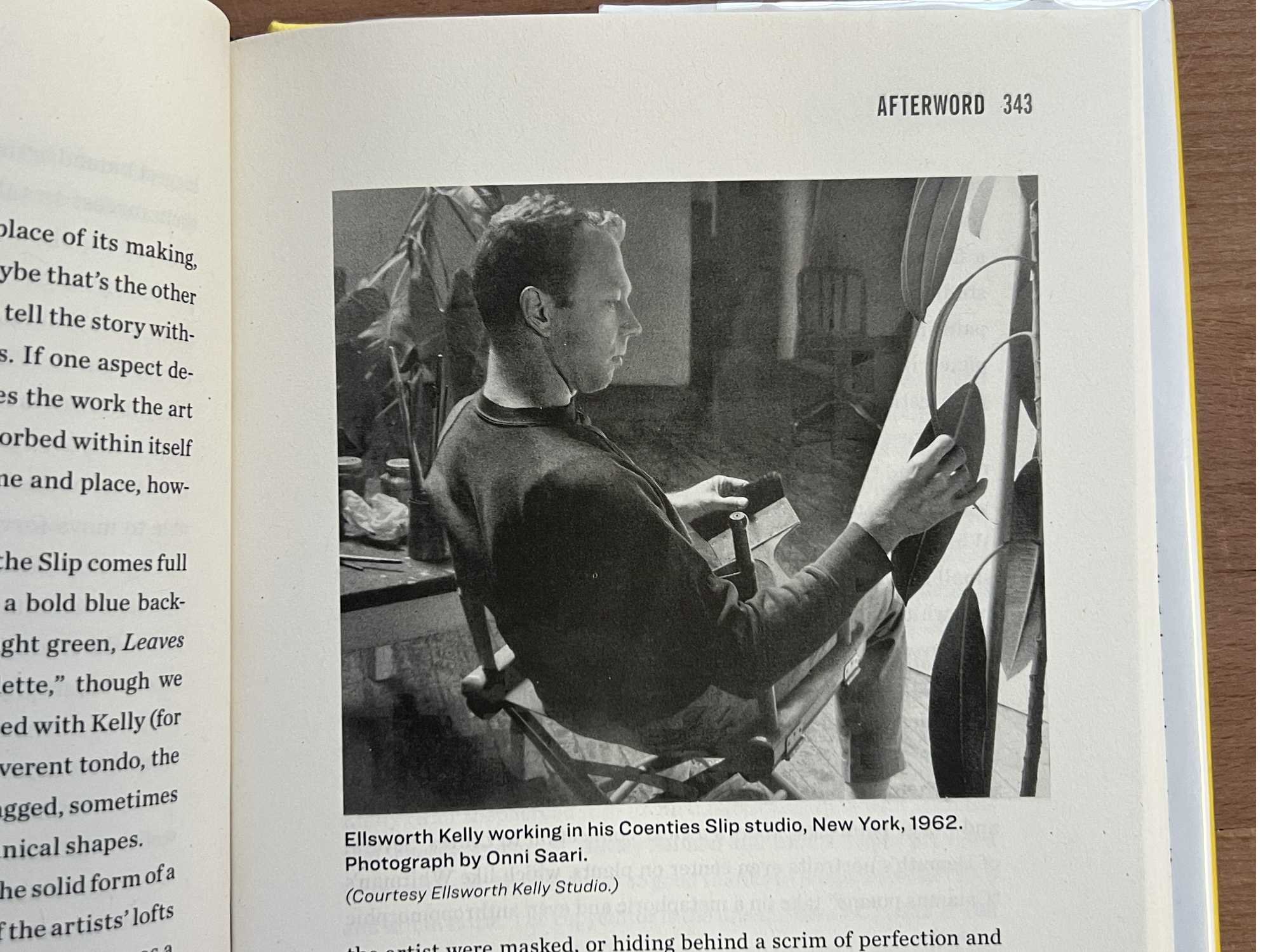

The Slip is a 2023 book by Prudence Peiffer that tells the story of art studios on Coenties Slip in New York City in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Slip, located at the very southern tip of Manhattan, was an in-between area that had been full of shipyards and sail-making factories, but was about to become the skyscraper financial district we know today. For almost a decade, artists filled many of the spaces, making work, community, and finding new paths forward for American art. It’s a fascinating, wonderful book that weaves together so much, including the stories of Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Indiana, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, and Lenore Tawney.

The following excerpt, from pages 134-135, details Agnes Martin’s exacting approach to art making.

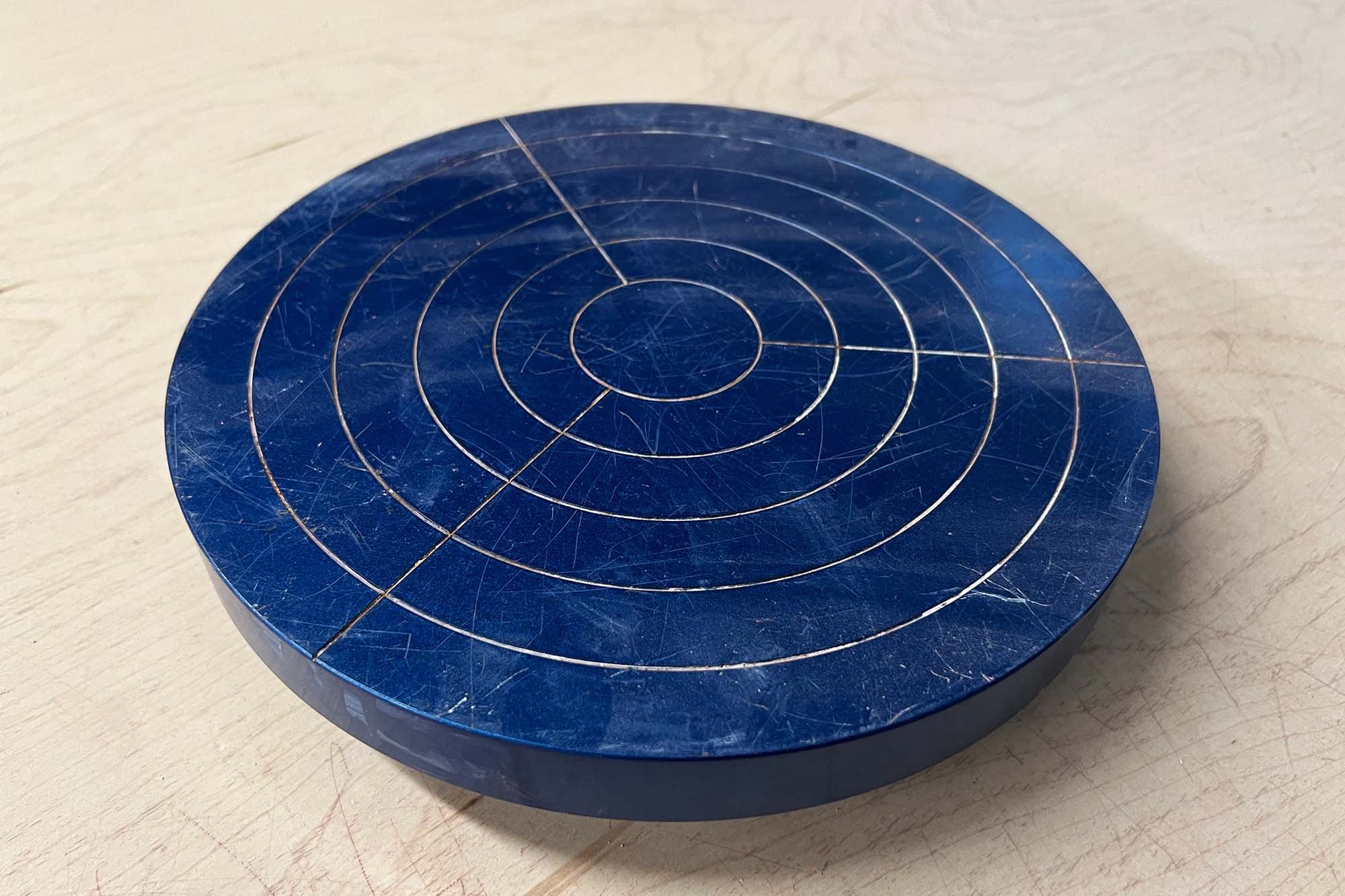

The stakes were always high for Martin. The artist Chryssa Vardea-Mavromichali, who went by her first name, remembered seeing paintings in Martin’s studio that she admired, but Martin had already rejected them because of a barely perceived texture on their surface. “When art becomes that austere, everything matters.” If a paintinjg wasn’t going well, Martin would quickly take a knife to her canvas. She could not stand to have things around her that didn’t work. A term that comes up repeatedly in her own writing, and for many that knew her, is perfection. (The critic Jill) Johnston wrote that the value Martin placed “on the known rather than the seen suggests innate ideas which she sometimes calls a memory of perfection.” (Jack) Youngerman remembered “Agnes was a perfectionist about her work.” This need for control was a strange way of negating a necessary step of any creative process—trials, failure—and, ironically for such a private person, a way of self-mythologizing, of “not admitting that you’ve ever done anything ordinary.” And Martin herself once said, “I paint about the perfection that transcends what you see—the perfection that only exists in awareness.”

Despite her frenetic approach, Martin’s canvases in this period grew larger, more modulated, serene even. She had, in her own description, eliminated everything from her landscapes until she was left with only the horizontal lines she liked, the horizons. In a review of her first solo show in New York in 1958 at Betty Parson’s Section Eleven gallery, a critic spoke of her “large quiet abstractions.” And Dore Ashton, reviewing that same premiere, got to the essense of what had been considered but wasn’t there—”The result of many years of refinement. She has eliminated all but essentials for her poetic expression.”

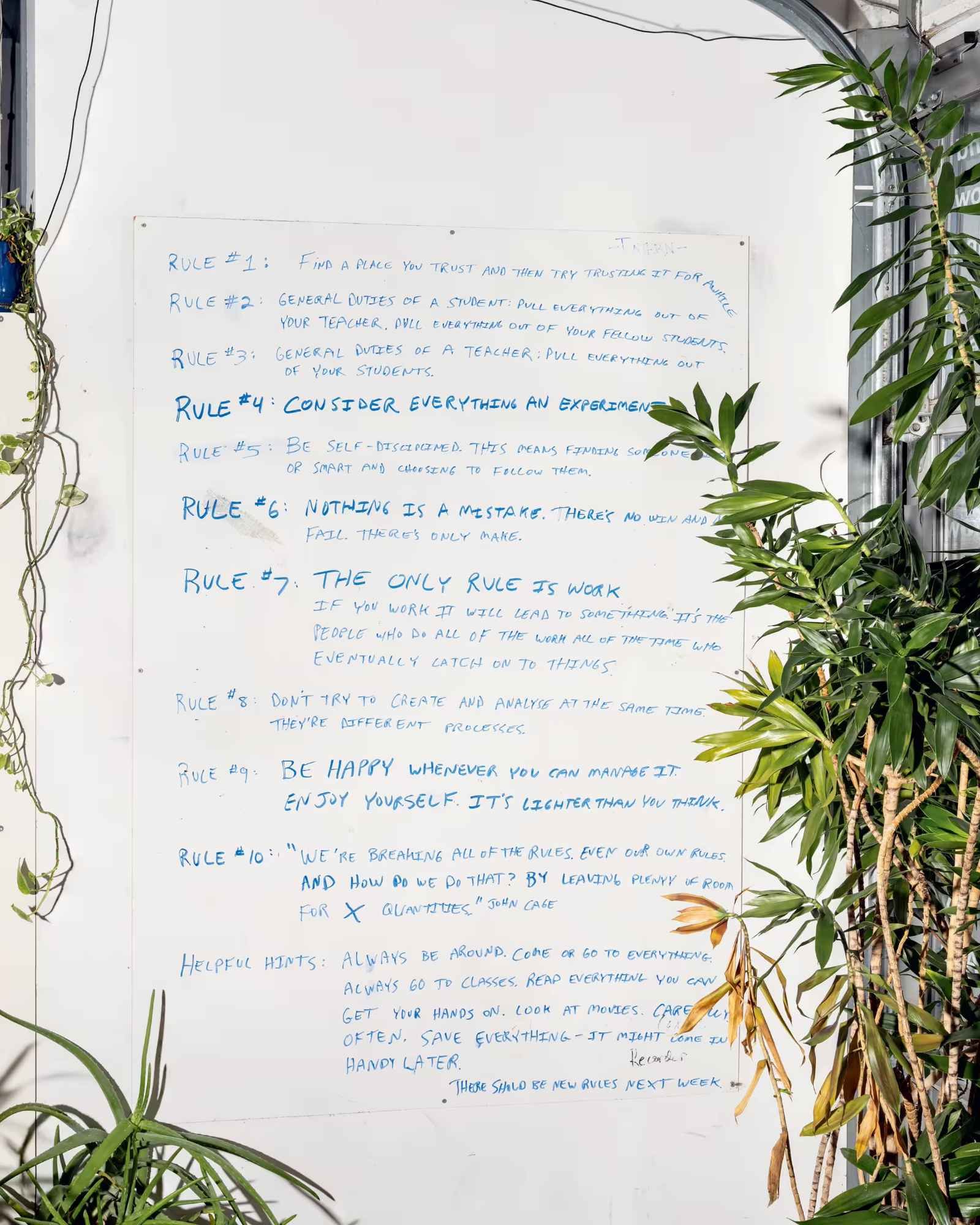

Martin required specific conditions to work. “In the studio an artist must have no interrruptions from himself or any else. Interruptions are disasters,” she explained in a lecture a decade after her time in New York. Her second Coenties Slip studio, at 3–5, where she moved in 1959, was “very quiet,” as Wilson remembered, with “an absence of agitation.” Entering it was like entering “large quiet,” with its white walls, gray floors, and homemade picnic table and benches. Everything needed to be calibrated. “You must be clean and arrange your studio in a way that will forward a quiet state of mind,” Martin insisted. And she wrote in her journal once that “the sentimental furniture threatens the peace.” The artist needed to get past “a lot of rubbishy thoughts” to the inner mind, where inspiration lay. “Composition is an absolute mystery. It is dictated by the mind.”

The cover of The Slip by Prudence Peiffer

The Slip: The New York City Street That Changed American Art Forever

By Prudence Peiffer

411 pages, published by Harper Collins, 2023

Shop the book new and used at the following links:

You might also enjoy:

Georgia O’Keeffe on making ‘ordinary paintings’

Wayne Thiebaud on how to avoid being an ‘art employee’

See all posts tagged Inspiration