Wayne Thiebaud is known for his iconic pop paintings of everyday American objects and though he was part of the generation of Pop artists that included Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, he maintained his independence from the New York art world (and never really thought of himself as a pop artist). He lived and worked in Sacramento and Davis, California, and in addition to paintings of cakes, gumball machines, and counter displays of pies and food, he also painted vertiginous San Francisco cityscapes, abstracted landscapes, and more. He was also a beloved professor at University of California at Davis. He passed away in late 2021 at the age of 101.

Pages 36-37 of Episodes with Wayne Thiebaud, including a reproduction of Pastel Scatter from 1972, a (lol) pastel drawing of sticks of pastels.

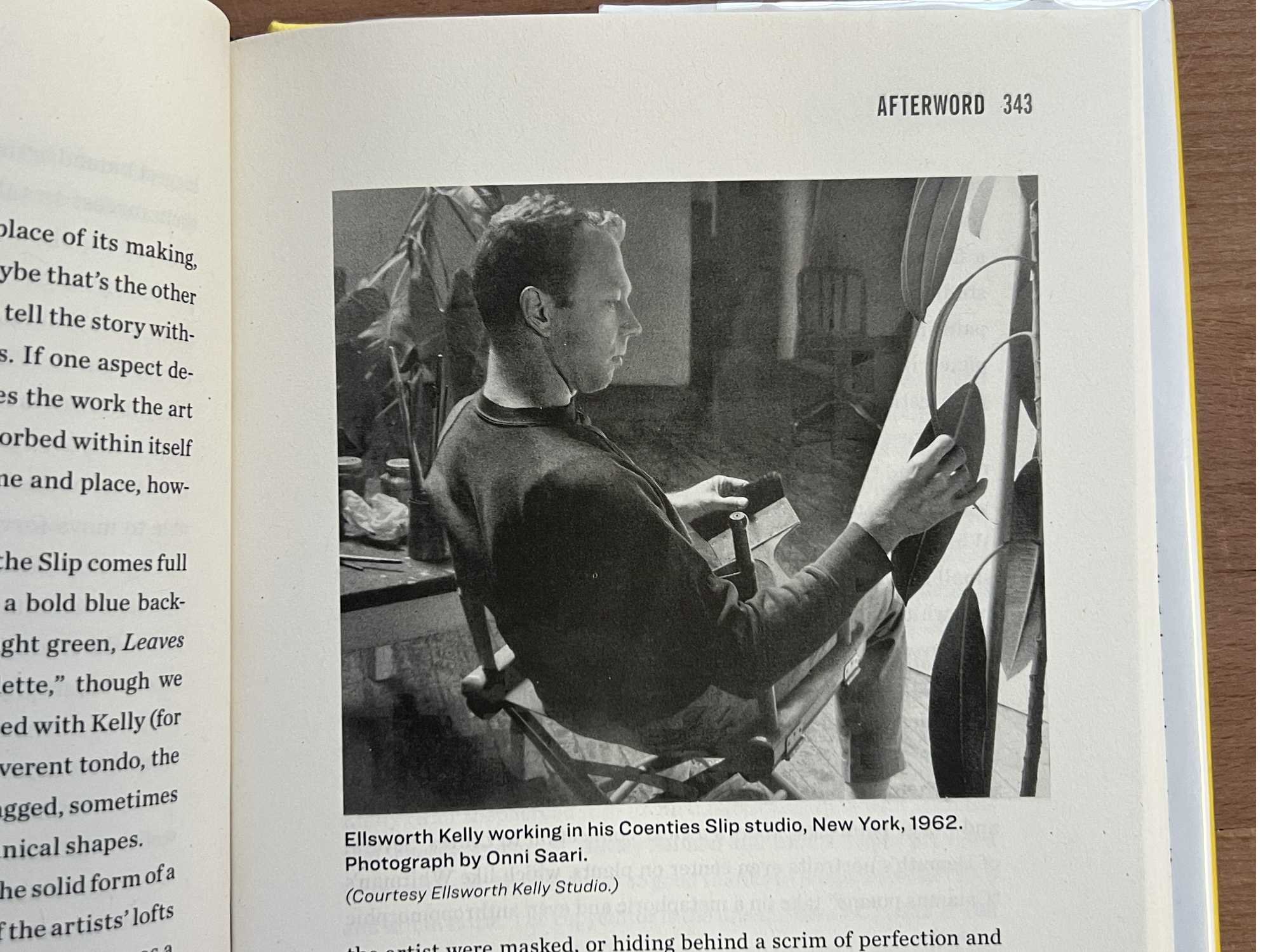

For the book Episodes with Wayne Thiebaud, (view book on Amazon) two of his former students, Eve Aschheim and Chris Daubert, conducted four conversations between 2009 and 2011 which were then lightly edited and published. The book includes lots of great quips and background on Thiebaud (such as he thought Jackson Pollock was a middling painter) along with reproductions of work by Thiebaud and some of his influences.

One of my favorite bits is from the beginning of the book, where Thiebaud details why he left New York City in 1957 after living there for a year:

Eve Aschheim: Why did you come back from New York?

Wayne Thiebaud: I missed space and tennis, and having a life. I was afraid, as I perceived it, which is maybe curious, that there was too much talk and focus on art rather than painting or sculpture or what I think we’re obliged to do. And I think the idea of an art employee is very dangerous.

Chris Daubert: What do you mean by “an art employee” — someone who works for the art world?

Pages 52-53 of Episodes with Wayne Thiebaud (Shop at Amazon)

WT: It refers to the dangers and seductions of the current art scene that can infer a kind of need to belong or be influenced by whatever its present preoccupations may be. And it can be an easy distraction away from what serious and unique directions painters’ personal researches and interests may take them. That, for me, is a disassociation from the percentage of those basically three worlds: the art of the self, the art of art history, and the art of your self (the art of your own artistic preoccupation), so that you get some kind of an equal mix. If they get out of balance, it seems to me you get an art employee, where you’re so saturated with “What should I do? What can I do? What might I do?” rather than saying, “Oh, I really feel I want to do and pursue art with the great tradition” —using that as a bureau of standards and inspiration and knowledge and tools, and combine those as best you can.

Later in the same interview, Thiebaud returns to this idea of the art employee who might end up making “light manufacturing products.”

EA: Your paintings have this incredible complexity, and at the same time the painting is fresh and everything’s at risk when you apply it. Is that something you have to struggle for?

WT: It is a lot like a golf stroke or a tennis stroke. That’s the basis of whyI believe so much in lots of drawing and lots of manipulative skills being developed. I know now there’s a big process on to deskill the artist—have you heard about that?

EA: Benjamin Buchloh has pushed this idea, which lots of people have taken up.

WT: [laughs] Risk. It’s something you just have to take into account, that you’re going to fail a lot and you can’t baby up to it. You’ve got to go for it, and then if it fails you either are stuck with it and you deal with it, hope that maybe you can bypass that area, or you just have to destroy it and start over, you just have to scrape it off. And that’s why de Kooning scraped off so many paintings. He never wanted to have it look labored or chintzed or—

EA: Safe.

WT: Yes, safe. And it’s very hard to get students to do that because it’s hard to do.

EA: It’s hard to simultaneously get the complexity of the composition.

WT: That’s right, but that’s why you have to think of de Kooning drawing so well; he had a rich vocabulary of forms that he could draw on, in addition to what he might be looking at. And we have got to get back to drawing somehow. I know there’s that other danger of learning to draw and then you can never do anything but that.

EA: A critic said that drawing is how to get out of Abstract Expressionism. The next generation of artists got out by drawing and the ones who continued to paint—and this happened several times in different historical periods—got stuck, while the ones who drew were able to find a new way.

WT: That’s true. I think as it became very easy to develop these light manufacturing products, and the temptation was great because it becomes a salable commodity again—and there you are trapped in that art world. Dealers don’t want you to change.

The back cover of Episodes with Wayne Thiebaud.

A few other great quotes from the book:

Thiebaud on drawing:

“Yes, I think everybody should draw. It’s such a terrific way of knowing things and testing what you know. It gives you access to so many things, that we’re just really cheating ourselves to not to teach people to draw…Once you get past the hurdle of people being terrified or bored by it, either one, and to find out it’s not mysterious… You can’t draw like Rembrandt, but you can really represent things, you can draw your things, find out about things. You can begin to see what your life is in terms of where you are in space and what things are, and ways to go. It really is a poetic exercise also.”

Thiebaud on learning technique

“When I used to work a lot harder with the students, trying to get them to do some of these things, I’d just point out, ‘Well, this is one of your muscles here. This is where you’re used to doing writing.’ I said, ‘Then you have this whole hand with all your fingers. That’s wrist. You’ve got to develop this universal wrist so you can come at it, under it, over it. Then you’ve got to the arm, from here, and what that can do or not do, and then you’ve got the shoulder.’ And all of those various motions you have to train so that you do it like hitting a golf ball.”

Thiebaud’s advice to painters:

“Get the hell busy, make lots of mistakes, do thousands of drawings—from the figure—even if you’re going to be an abstract painter. Learn things about grace, pressure, tension. Don’t be afraid of making lots of mistakes. Don’t be afraid of being influenced. Copy pictures. Enjoy the hell out of it.”

This book is full of lots of great ideas and quotes from Thiebaud. It’s a must for any Thiebaud fans or for students of painting.

Episodes with Wayne Thiebaud

by Eve Aschheim and Chris Daubert

104 pages, 2014, Black Square Editions