British artist Richard Hamilton gave a talk to students in 1971 during his show “Metamorfose van het object” at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. The talk was recorded by Jef Cornelis and a transcript was first published in a 2014 catalogue that accompanied a Tate Modern retrospective of Hamilton’s work. Here’s an excerpt of that text along with part of the introduction by Mark Godfrey. The whole text can be found in the catalogue.

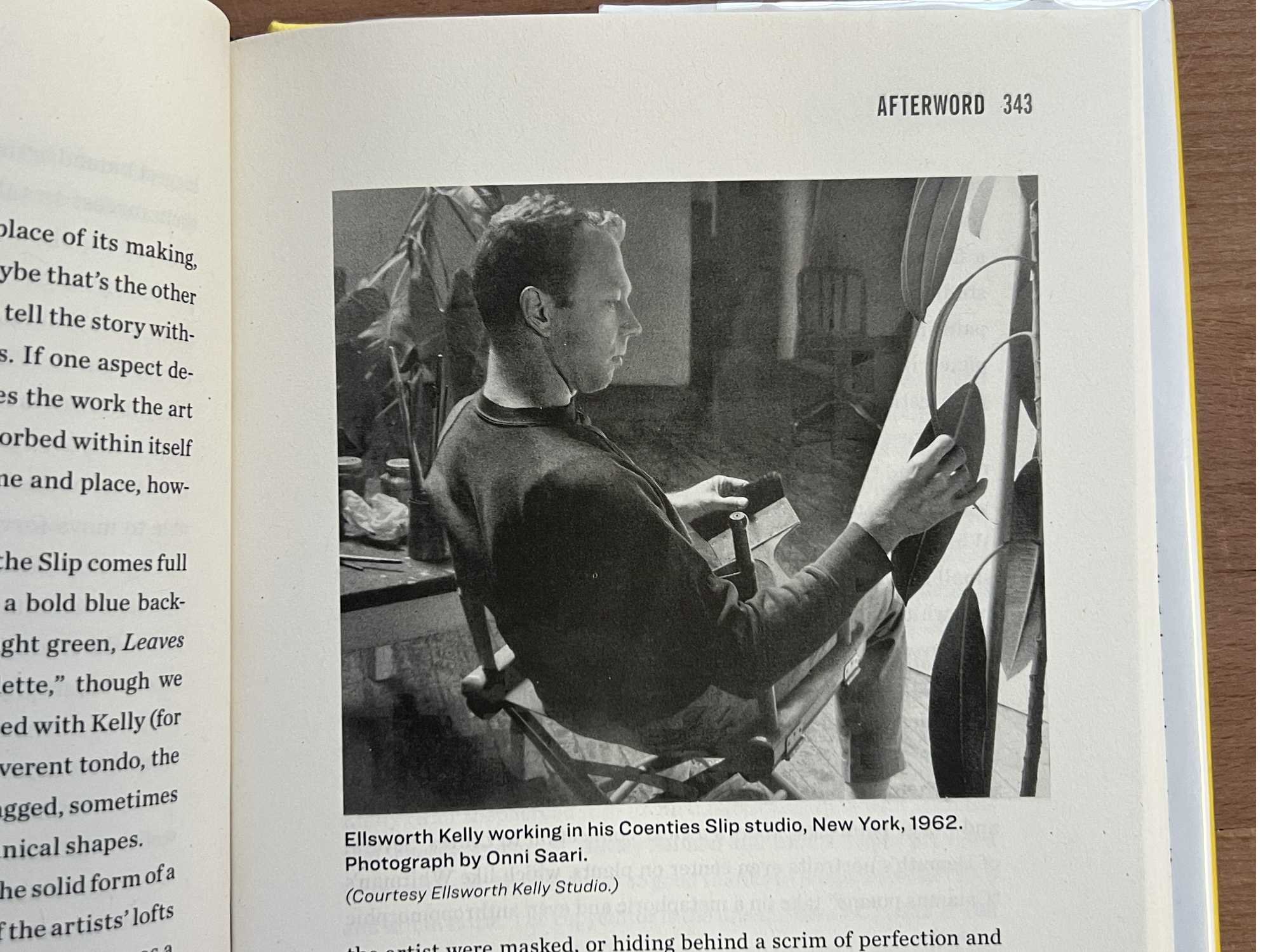

Richard Hamilton at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, 1971

From the introduction by Mark Godfrey:

Hamilton begins with a succinct analysis of four categories of painting that he deploys in his work: figuration; diagrammatic representation of information or space; painting which foregrounds the material qualities of paint; and semiotic painting, where a work might include signs or words. Remarkably, Hamilton shows that each kind of painting can be useful (and deployed without parody or quotation) even if he does not subscribe to the belief system around it. He acknowledges the Abstract Expressionist mark for instance, even though he does not find a drip of paint to be “sensuous.” Other European artists were beginning to juxtapose different kinds of abstract strokes to represent modernism as an exhausted set of options (for example Sigmar Polke) but no one else was putting together these four kinds of painting to explore their different functions.

Another still image from the film of Richard Hamilton’s 1971 talk.

Hamilton later connects his tendency to make different versions of a work and his skepticism towards a signature style…Many of the Conceptual artsist would have criticized such a work, and painting in general, but at the end of this talk Hamilton comes up with an extraordinary justification of painting through the language of Conceptual art. If anything that documents an artist’s thought is a work of art, then ready-made, a neon text, or photostat of a dictionary definition is no more or less valid an art work than a painting. With razor-like thinking Hamilton cuts through the discourses of the tie that would deny works like his own their place among radical practices.

Richard Hamilton:

I find that everything I do is concerned with one of four means of representation, that is, concerned either with one way of doing something or with a number of ways superimposed on one another. The first way is probably pure figuration, pure photographic rendering—the kind of traditional way in which people perceive the world and the way they perceive and experience of the world through a two-dimensional surface. A lot of the work that I have done is concerned with photography. Rather than paint it in a laborious kind of way, I say: “All right, I know that we can paint it but the camera can do that kind of job perfectly well.” So very often I find myself using the camera at the one level: information about imagery.

Then I find that there’s a geometrical approach, a diagrammatic way of providing information or receiving information—so that perspective is sometimes elaborated in a very precise way. Then there are occasions when I remember that paint itself has some quality, that the medium of paint is important; American Abstract Expressionism was concerned almost entirely with that plastic quality of paint. So I put paint in a very direct way onto a photograph or onto a drawing. But I don’t think I use it for a sensuous enjoyment of the paint. I’m saying that there is that other response to paint, and if I put it on, on a print or on a painting, I feel that it’s kind of token, it’s a representation. It simply signifies that kind of mark is a category: the plastic quality of the paint.

There are also other ways of receiving information. For example, a cross is a mark which has some plastic quality, but it also means something—it has a meaning as a sign: it means “no”, so a tick means “yes.” I think that signs appear sometimes in my work. Sometimes I’m interested in language expressed in a literary form. So some of these prints have words attached to them, and what I think they’re all about, really, are ways of communicating at a visual level. The interest for me in painting is to explore the whole of that territory, rather than to find a style which I can say is my own and to go on working in that vein. In a way, I try to exploit my talents: I think that it’s possible to use any kind of technical facility, any skill of handling that I might have received from institutions, even those which have a rather bad reputation. These days no one has any respect for the Royal Academy in London, but I have a very high regard for the skills it gave me, because I like to think that I can do a certain number of things. I feel I can do what I want to do because I have this technical facility given me by an education in a very stuffy academic art school.

And from the end of the talk:

A lot of artists now, I think, don’t look at the world directly. The paintings up to the end of the nineteenth century were all a direct experience of the world. People looked at the world and they experienced something and they tried to record that experience. But now I think the general experience of the world comes through magazines, through television, through cinema. There are many ways of experiencing the world, but the most important ways now are these secondary ways. The direct way of perceiving the world is of less importance to everybody, and I think that’s very significant…

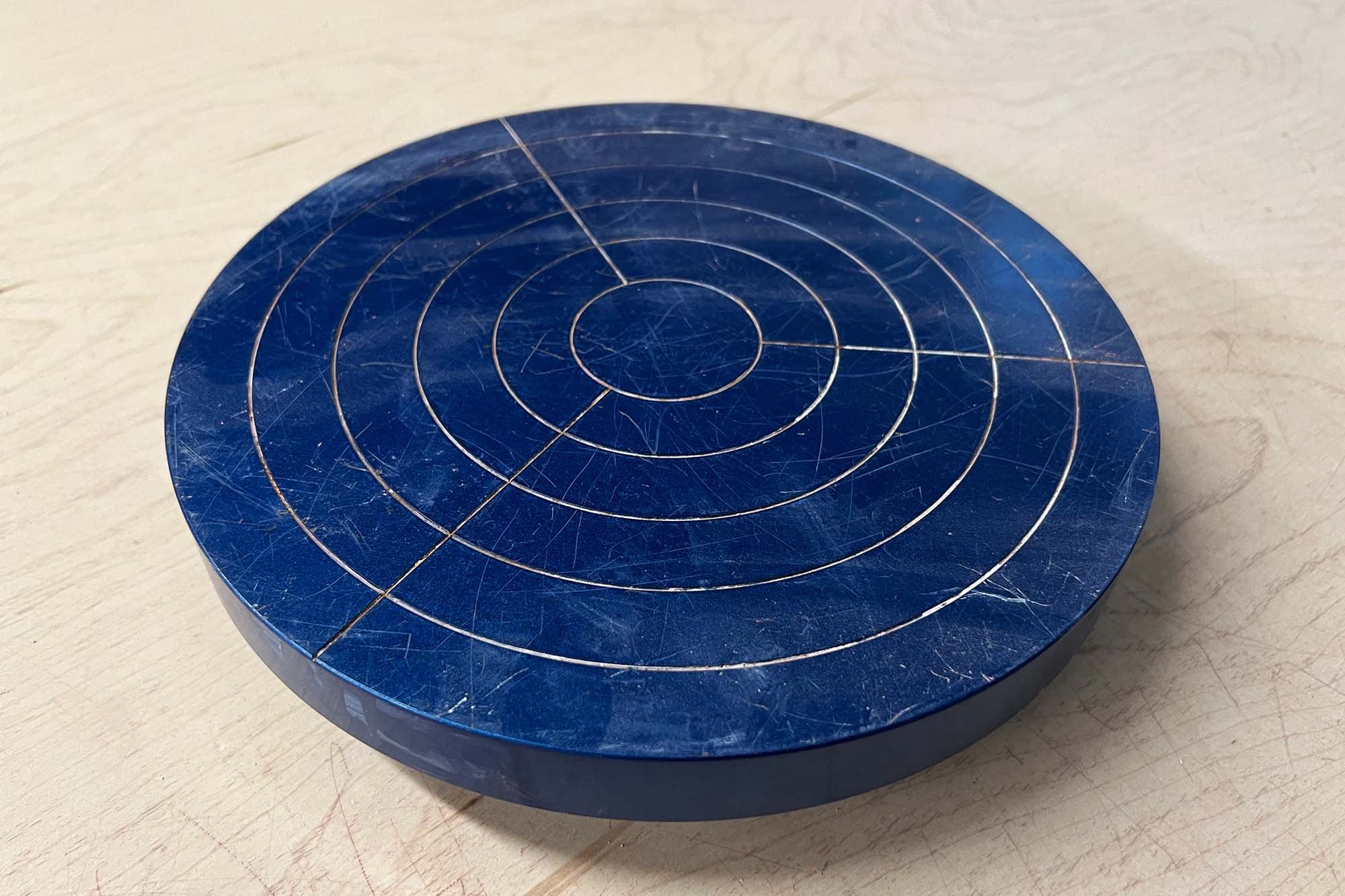

Pages 206-207 of the Richard Hamilton catalogue, published in 2014.

There’s an exhibition in Nuremberg at the moment and I suppose a lot of conceptual art will be there. The theme of the exhibition, because it’s on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of Dürer, is a statement they’ve taken from Dürer: “What beauty is, I don’t know.” And so I’ve tried to think not only what beauty was but also what art was and is now, at this present time. I decided first of all that a work of art is really no more than evidence that somebody has thought of a work of art. I think Duchamp establishes that the work of art itself is of no importance, because the work of art can change. It changes after its production through , in the first place, decay, and it also changes because the people who look at it change. This is one of the facts that one accepts about a work of art, now that we understand that it isn’t a permanent, timeless thing. So that you can say only that the work of art is telling you something about what the artist thought. What is important about the work of art is that it carries some thread, some information, from the mind of the artist.

One has to say: “This is what’s important—it’s what happened in the artist’s mind that is important, not what happened on the piece of paper, or that canvas, or the object. This is an intermediary vehicle.” I’ve carried this process further and said that anything that communicates an artist’s thoughts is a work of art. It doesn’t need even to be made by the artist—it doesn’t need to be in any particular style, because you can work in another person’s style and it will still be a work of art. You can work ironically or seriously you can do anything—anything is possible. The only thing that’s important is that what is produced is a document which relates to an idea. I ended up by saying that a painting is evidence that an artist has proposed a work of art. And I don’t see why a painting isn’t just as good evidence that a work of art has been produced as, well, any other kind of activity that artists can engage in.

… Is that enough?

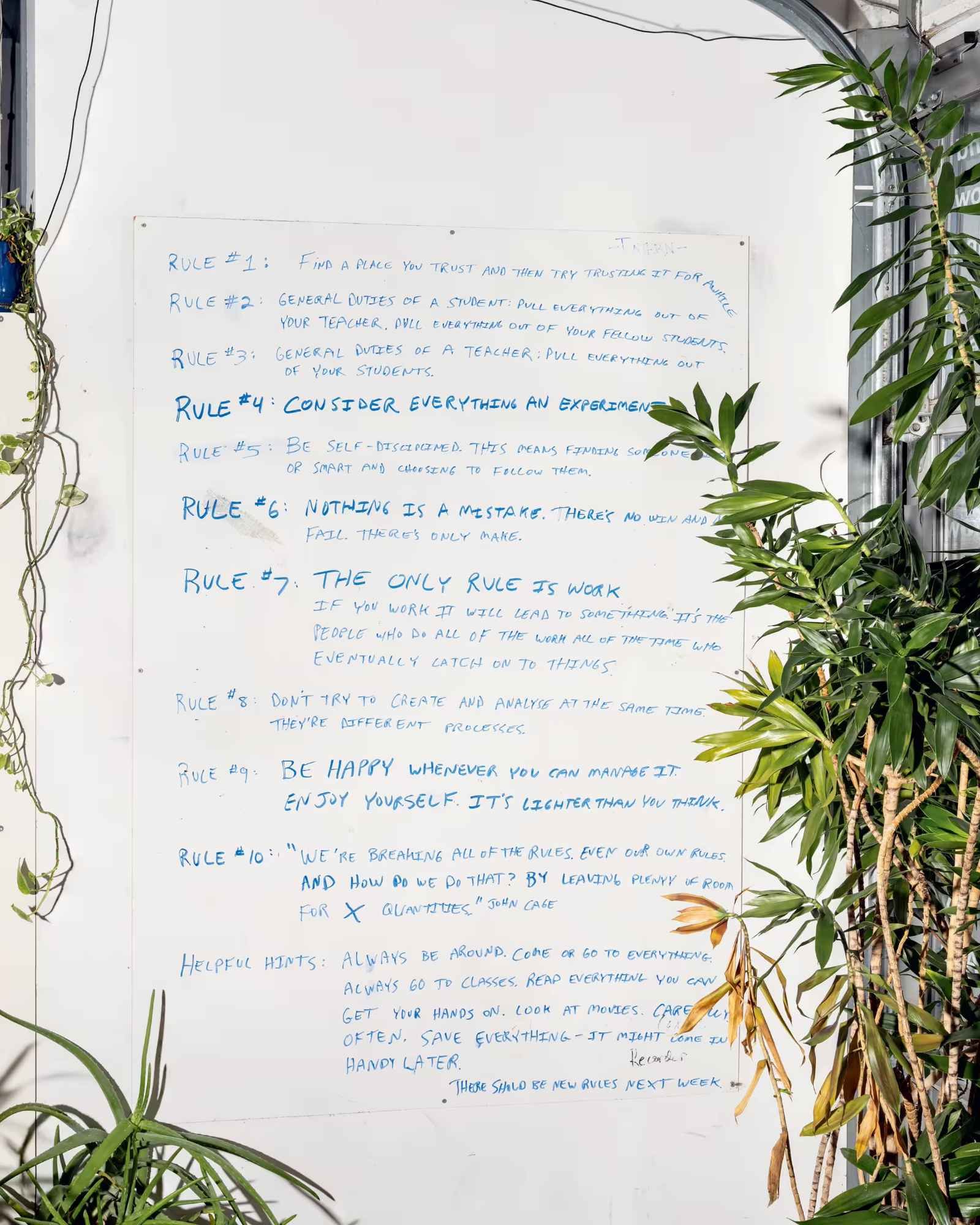

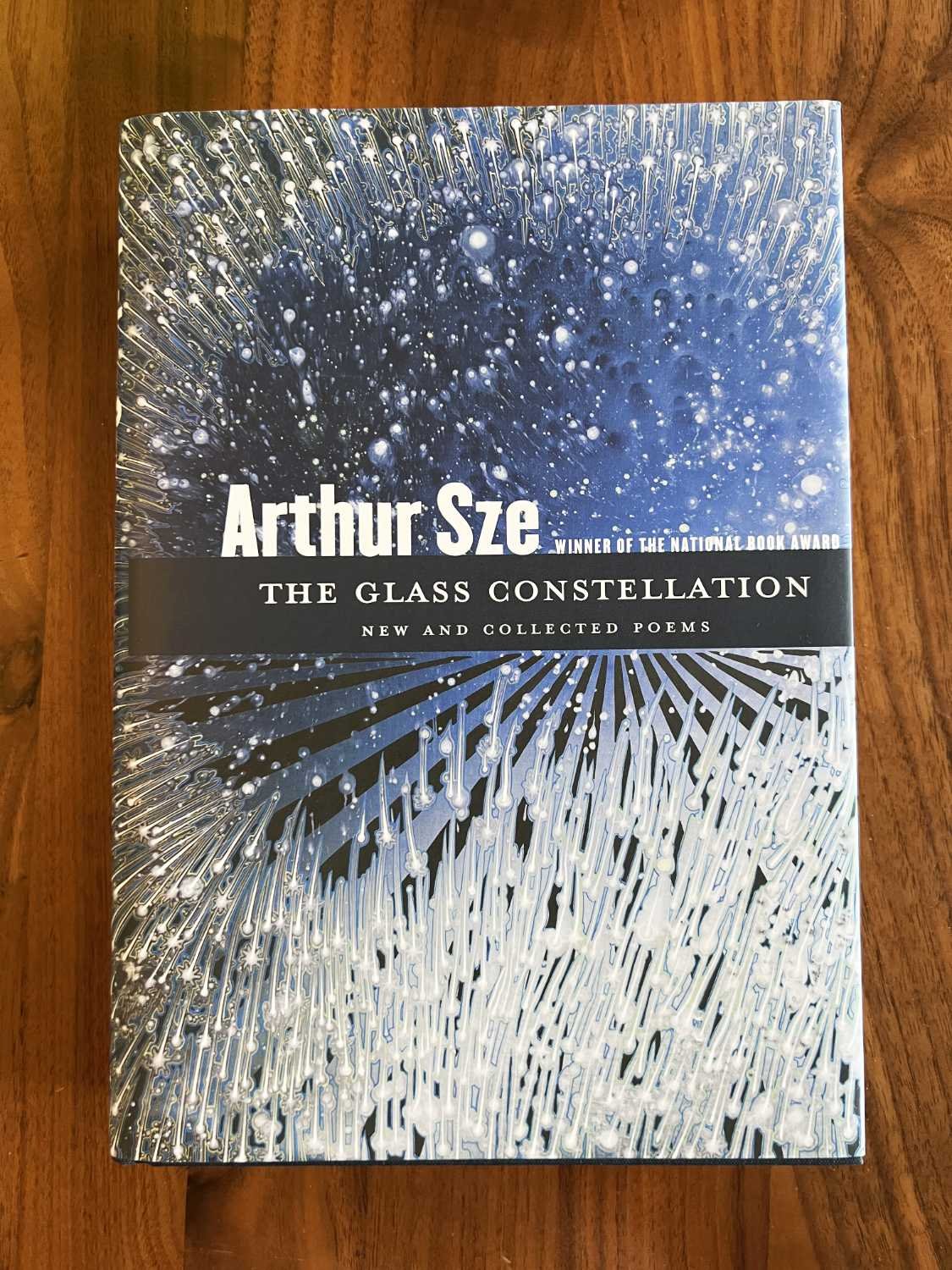

The cover of the book.

Read the entire statement in on pages 201–207 in the catalog Richard Hamilton, 2014, published by the Tate Modern.

The catalogue includes numerous images and reproductions of Hamilton’s work, an introduction by Paul Schimmel and essays by:

Victoria Walsh

Benjamin Buchloh

Alice Rawsthorn

Hal Foster

Mark Godfrey

Fanny Singer

What do you think about Richard Hamilton’s statement? Let us know in the comments.

You may also be interested in:

A Time For New Dreams by Ben Okri

Shoji Hamada on making pots.

Centering by M.C. Richards.

For more posts like this, click here.