In the essay On Color, New York-based artist Amy Sillman has what may the best description of what it takes to make an artwork:

Making a painting is so hard, it makes you crazy. Before even the vicissitudes of color, you have to negotiate tone, silhouette, line, space, zone, area, layer, scale, speed, and mass while interacting with a meta-surface of meaning, thought, text, sign, language, intention, concept, and history; you have to go your own way, to cut away from your heroes and influences, and still be utterly conscious and literate about the discourse. You have to simultaneously diagnose, predict and ignore the past, present and future, all at once; you have to remember and to forget at the same time. You have to both deny and embrace all your impulses toward romanticism and irony; you have to both love and hate your objects and your subjects, to believe every shred of romantic and passionate mythos about painting and at the same time to cast a gimlet eye upon it.

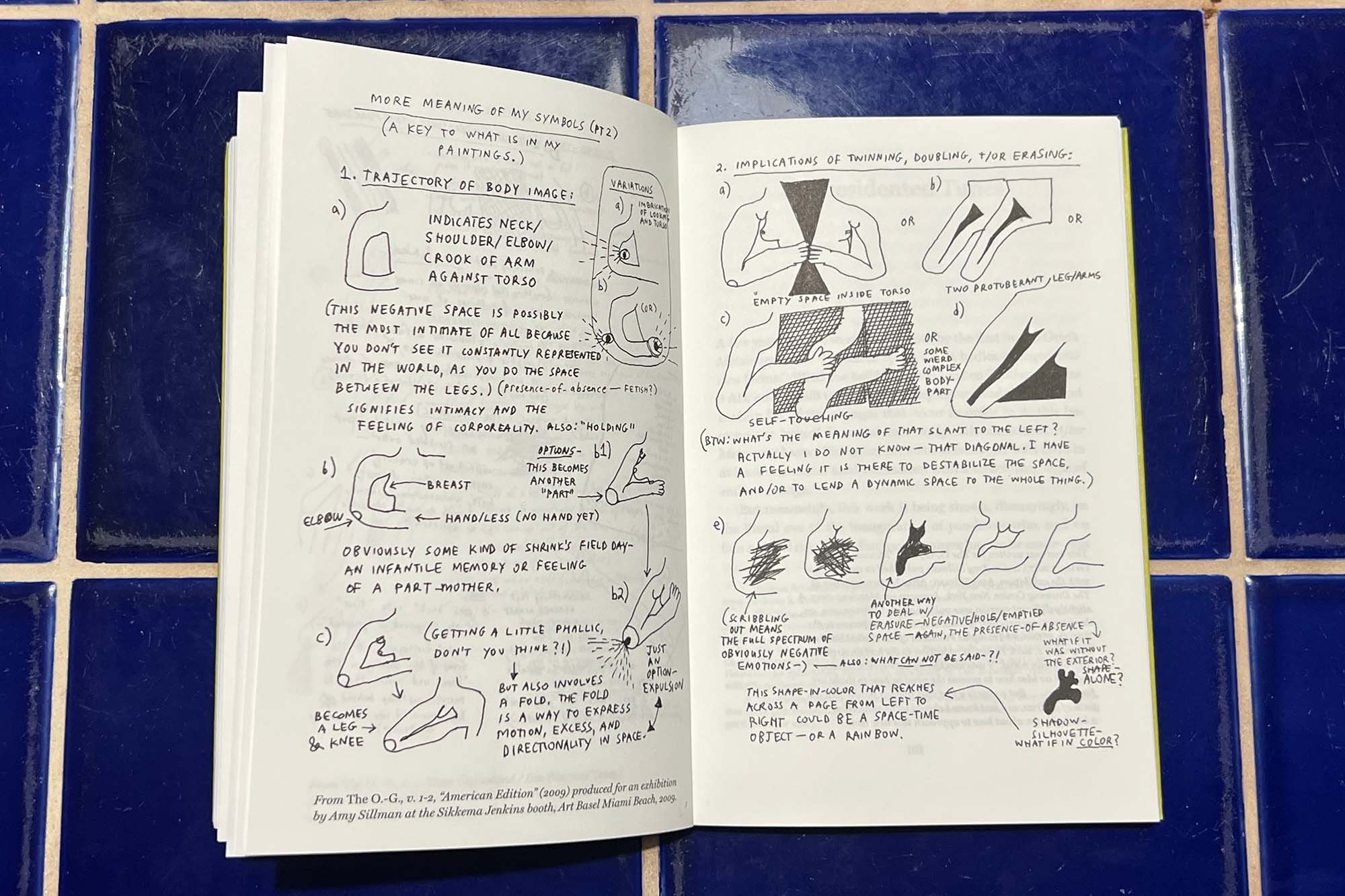

The book contains drawings and essays by Amy Sillman.

The book has 17 essays, including On Color and Further Notes on Shape, an essay Sillman wrote in conjunction with a 2019 group show Sillman curated at MoMA. In Further Notes, Sillman writes about a theory of “draw-ers” vs. painters:

For a long time I’d been nurturing a second idea, too, that somehow got nested in these thoughts: that you could divide artists into draw-ers versus painters, and that draw-ers were a subculture. Painters, it seemed like, work from an idea, moving deductively from the big picture down to the details in order to produce or construct an image they have in mind. Draw-ers, on the other hand, work from the weeks outward, building up from particulars, inductively, scratching and pawing at their paper with tools the scale of their hands. OR maybe they never get to a bigger picture at all, but move sideways, abductively, from a particular to particular. This made drawing itself seem like an activity not founded on logic but made up of contingencies, overflow: stray parts—a process that might be described as working blind, like a mole, or like a beaver building a thatch, rather than someone with an overarching worldview.

Later in the essay, Sillman addresses the idea that drawing and making is a political act as much as any other form of artmaking.

Maybe artist fussing over shapes are not the same people we first think of when we think of political art. But they make lumpen form that registers protest, they make gestures of care and repair, or they merely try to beam out an electrifyingly personal and strange signal that wakes up the receiver for a moment—one weird moment that could shift the sense of things, and thereby alter the world, even if only slightly. That sounds urgent to me.

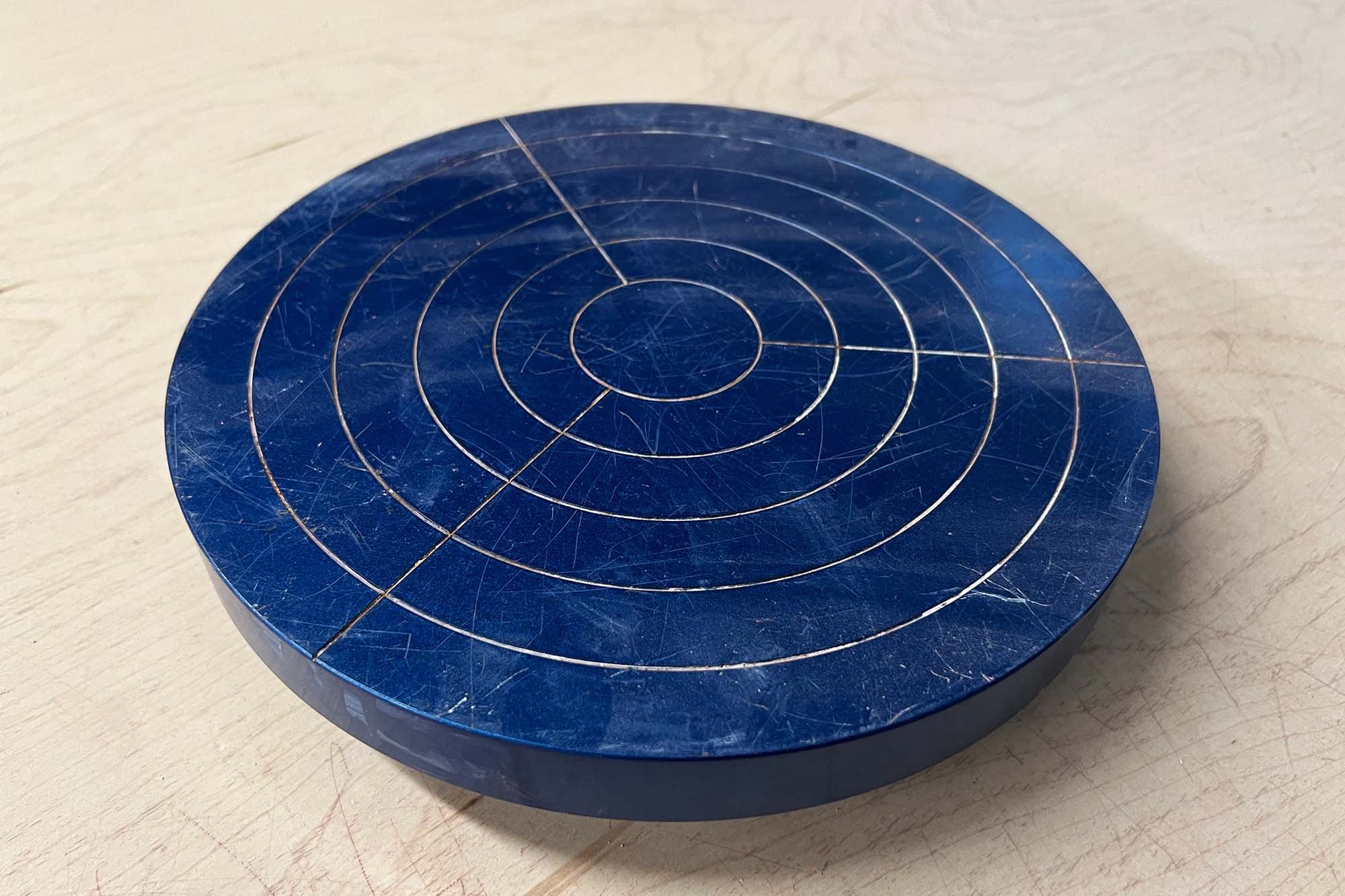

The book also contains a variety of diagram drawings by Sillman.

Faux Pas., Selected Writings and Drawings

by Amy Sillman

256 pages, paperback, 2020, After 8 Books

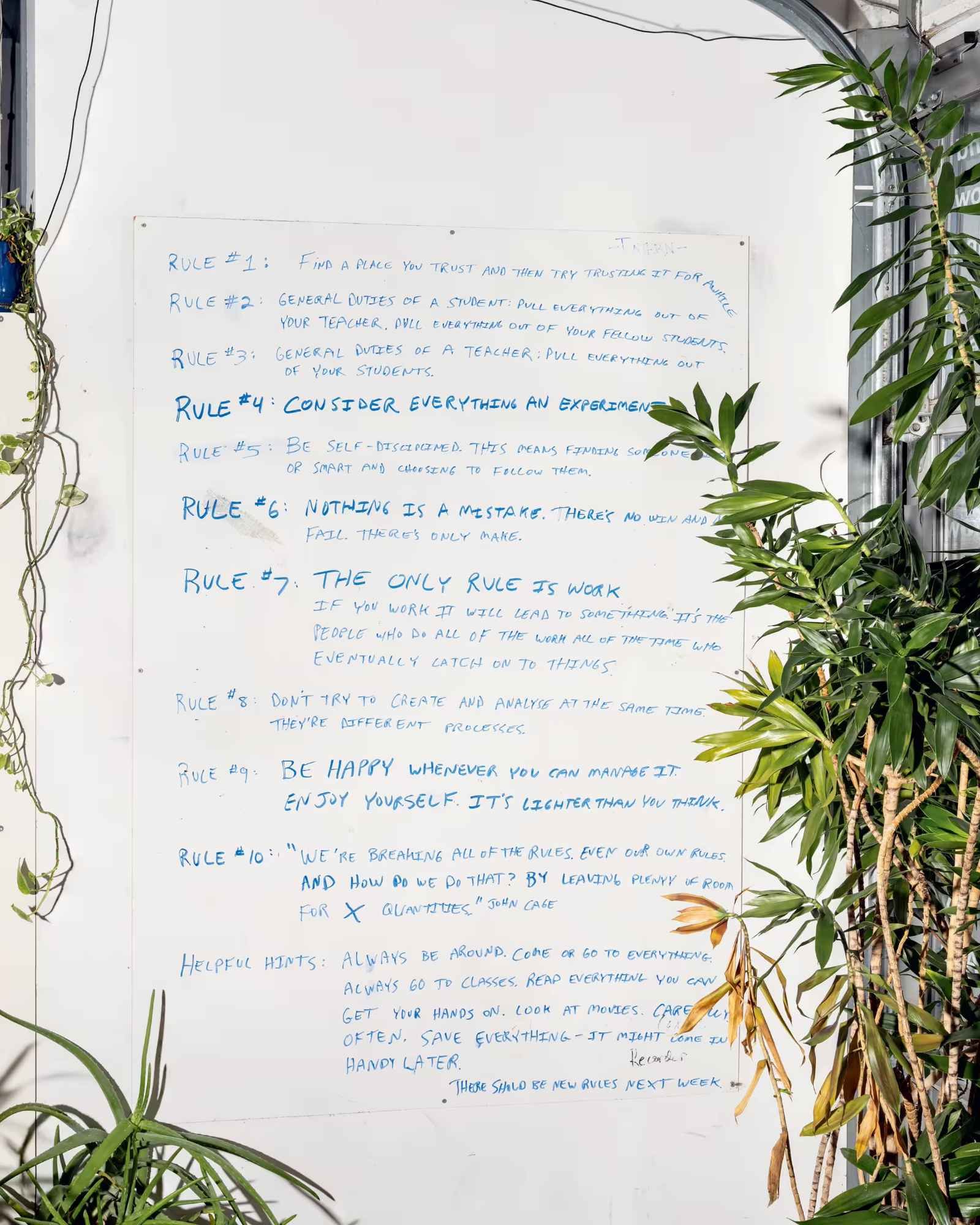

The back cover of Faux Pas. by Amy Sillman