Potato is a 2008 history of the “propitious esculent” by John Reader that covers the entire history of the plant, which originated in the Andean highlands of South America and was eventually exported and cultivated worldwide. On pages 51 and 52, Reeder addresses potatoes as a subject matter in Moche ceramic art. The Moche culture flourished along the coast of present-day Northern Peru from around 200 BC to 700 AD, and is known for its amazing array of ceramic vessels.

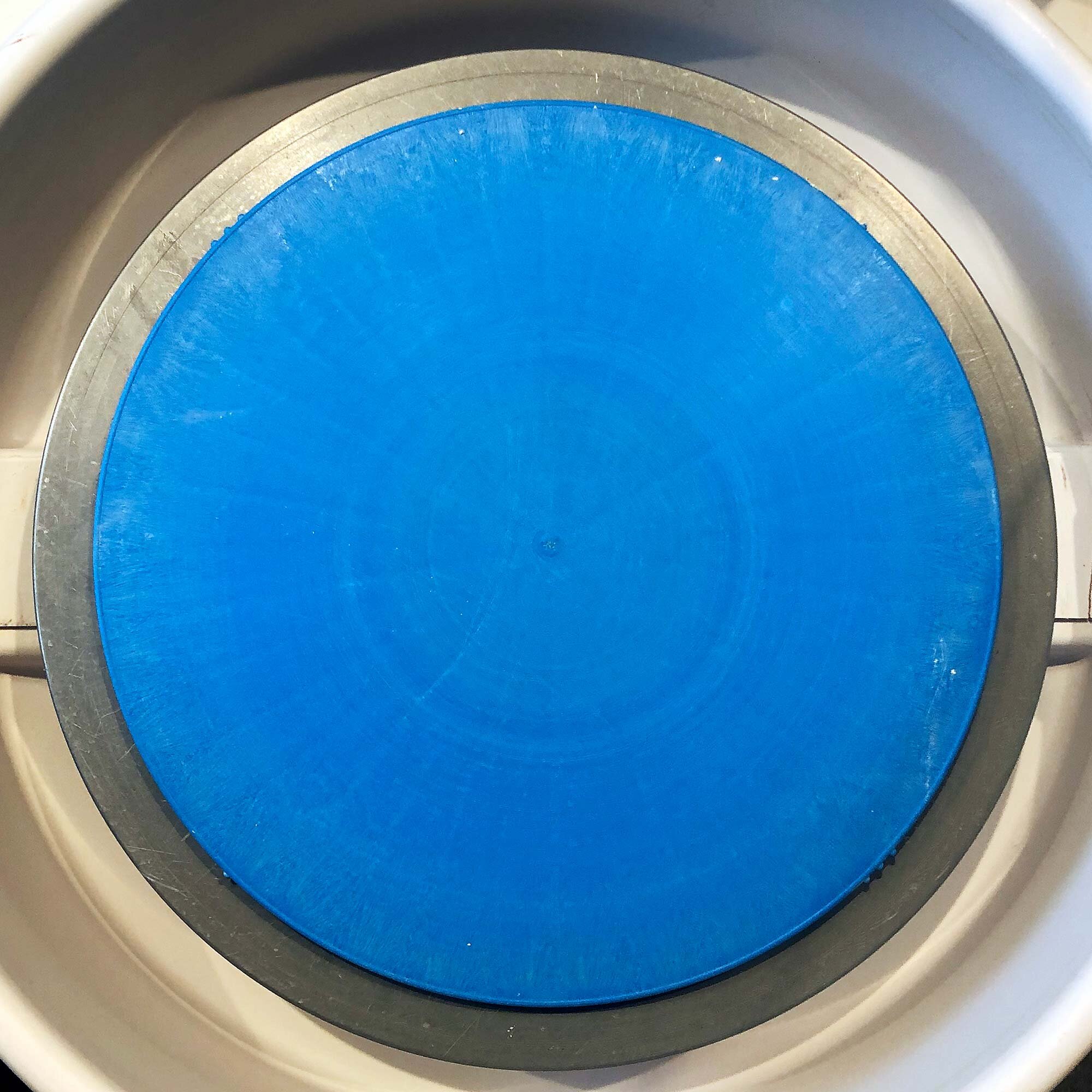

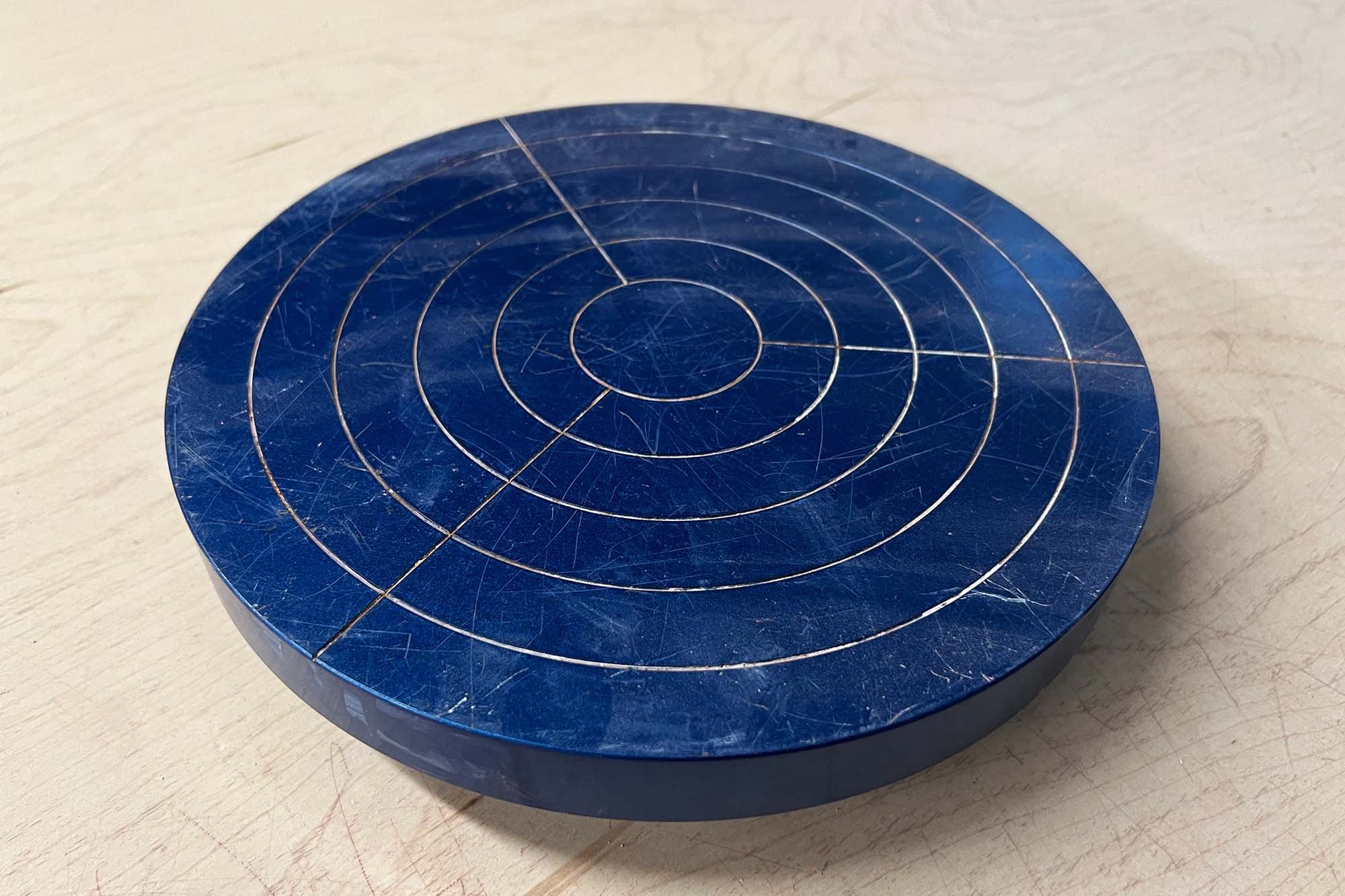

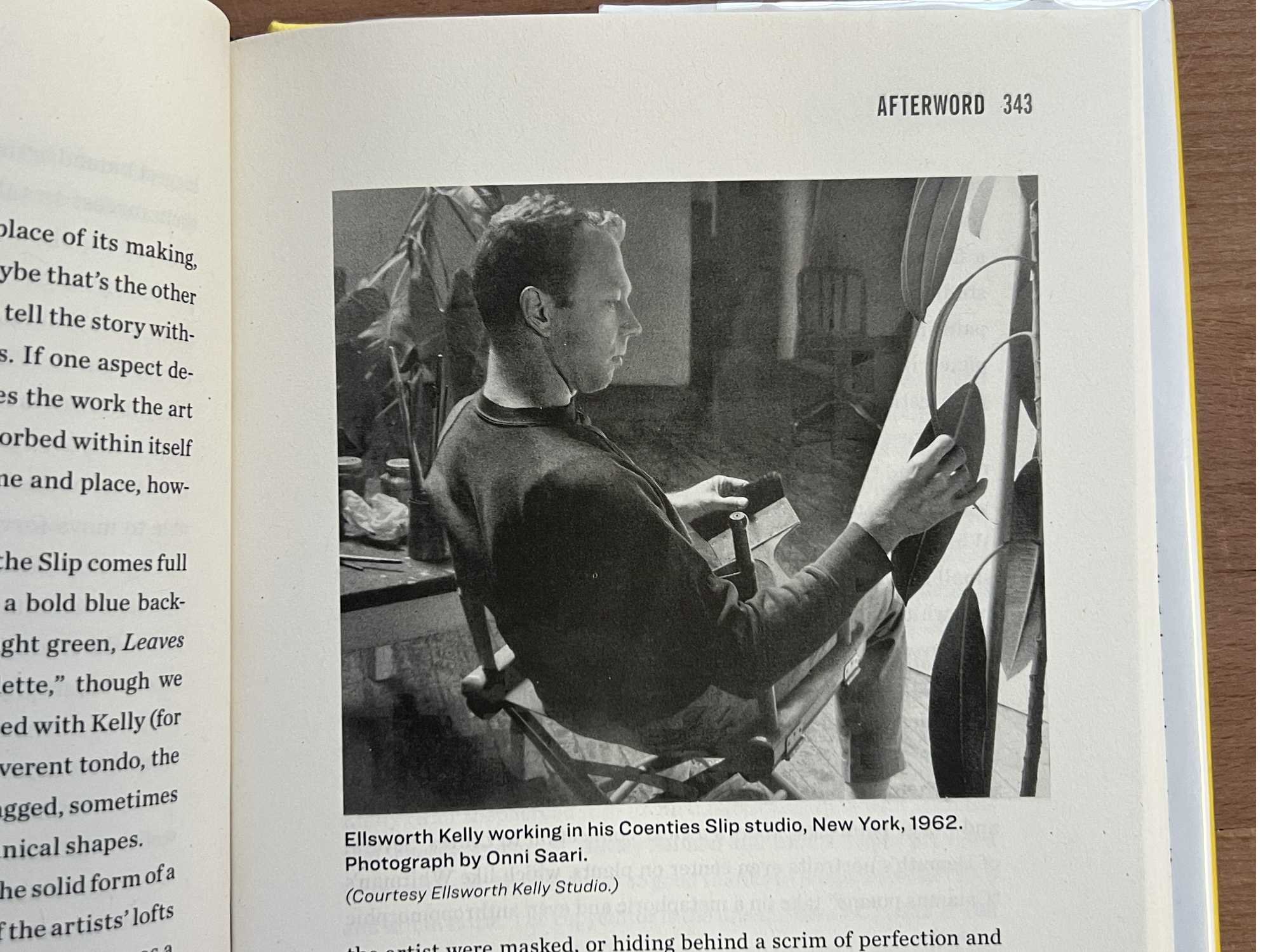

A Moche stirrup vessel with four potatoes from the Museo Larco in Lima, Peru.

“There was art too — paintings, sculpture, carvings, tapestries and wonderful ceramics. A diverse series of ceramic styles evolved, each with a wide range of examples, but the most interesting from the point of view of this narrative is the pottery of the Moche, who ruled the coastal and immediate inland regions of northern Peru from the beginning of the Christian era until about AD 600. The Moche took the potter’s art to an exceptionally high standard, producing vessels whose purpose must have been more decorative, or ceremonial, than utilitarian. Every aspect of Moche life is depicted in finely worked clay: men in the fields, people chasing deer with spears and clubs, hunters aiming blowguns at brilliantly feathered birds, fisherman putting to sea in small canoes, craftsmen at work, soldiers in battle, and scenes of human sacrifice — all beautifully painted and burnished. There are also scenes of people being carried in sedan chairs, seated on thrones, receiving tribute and engaging in sexual activities both commonplace and remarkable — all shown in exquisite detail.

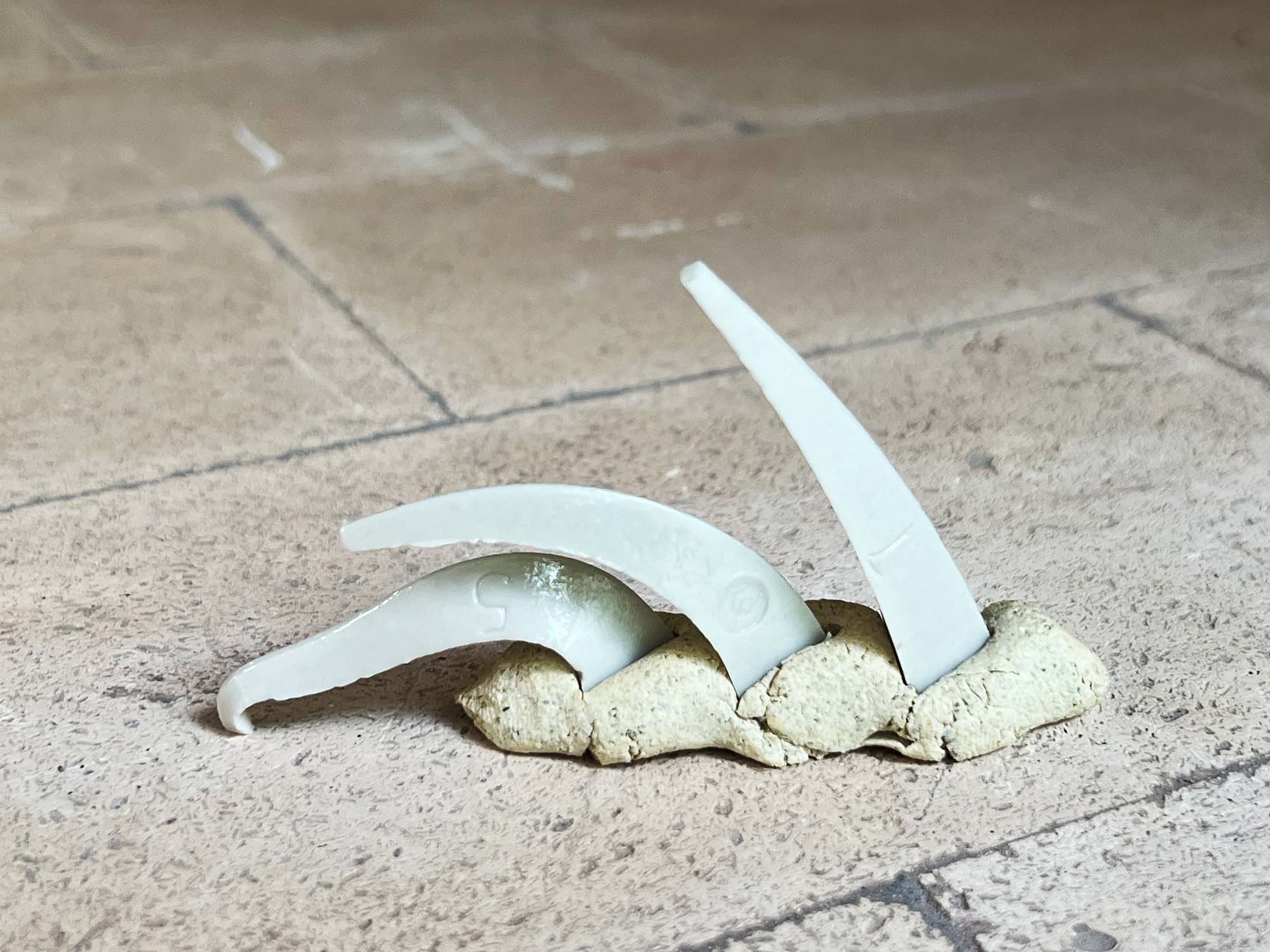

Potatoes feature prominently among the Moche ceramics. Of course, the tuber’s globular form is easily reproduced, and there are plenty of what might be called conventional potato pots, in that they are shaped like a potato, but there are also some oddities that combine the potato and the human form in a disturbing manner. The simplest just make a head or face of the potato, or use naturally occurring shapes to represent a human form — like the tubers that occasionally turn up with knobby heads or limbs attached — but others are more sinister. On one, several heads erupt through the skin; on another, a man carrying a corpse emerges from the deeply incised eyes; a ‘potato’ head has its nose and lips cut off; potato eyes are depicted as mutilations…

We can never know whether any particular significance should be attached to the combination of human and potato forms in Moche pottery, but surely must agree with an authority on most things relating to the potato, the Cambridge scientist Redcliffe N. Salaman, who concluded that the pots illustrate ‘the overwhelming important to certain sections of the population of the potato as a food . . . to the people both of the coast and the sierra’ — especially in times of famine or war. For, as we know, the potato could not be cultivated on the hot and arid coastal desert. Imports from the highlands were the only source, and for coastal people who had become dependent on the potato, a disrupted supply could spell disaster.”

Potato: A History of the Propitious Esculent

by John Reader

2009, Yale University Press, 315 pages