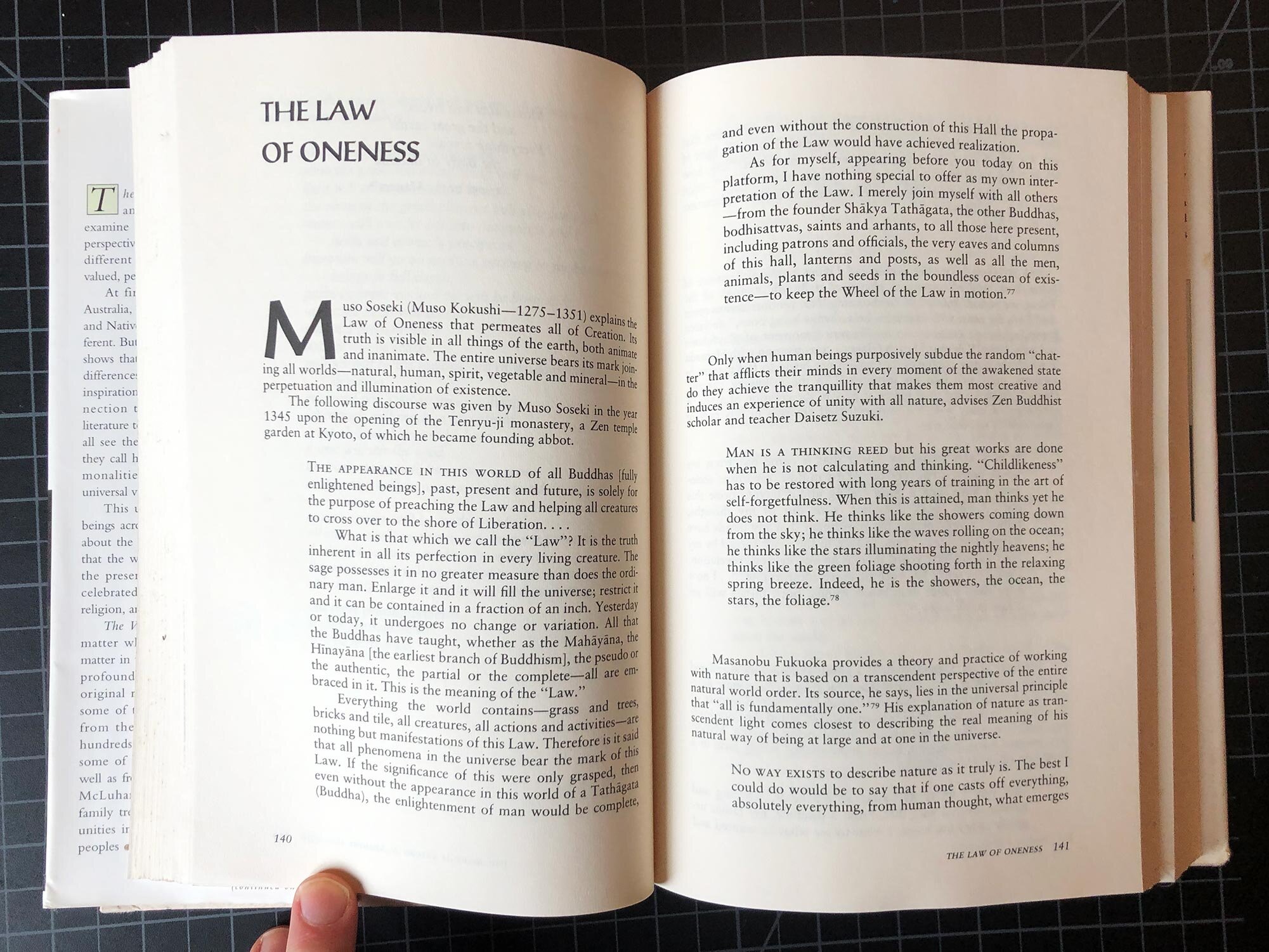

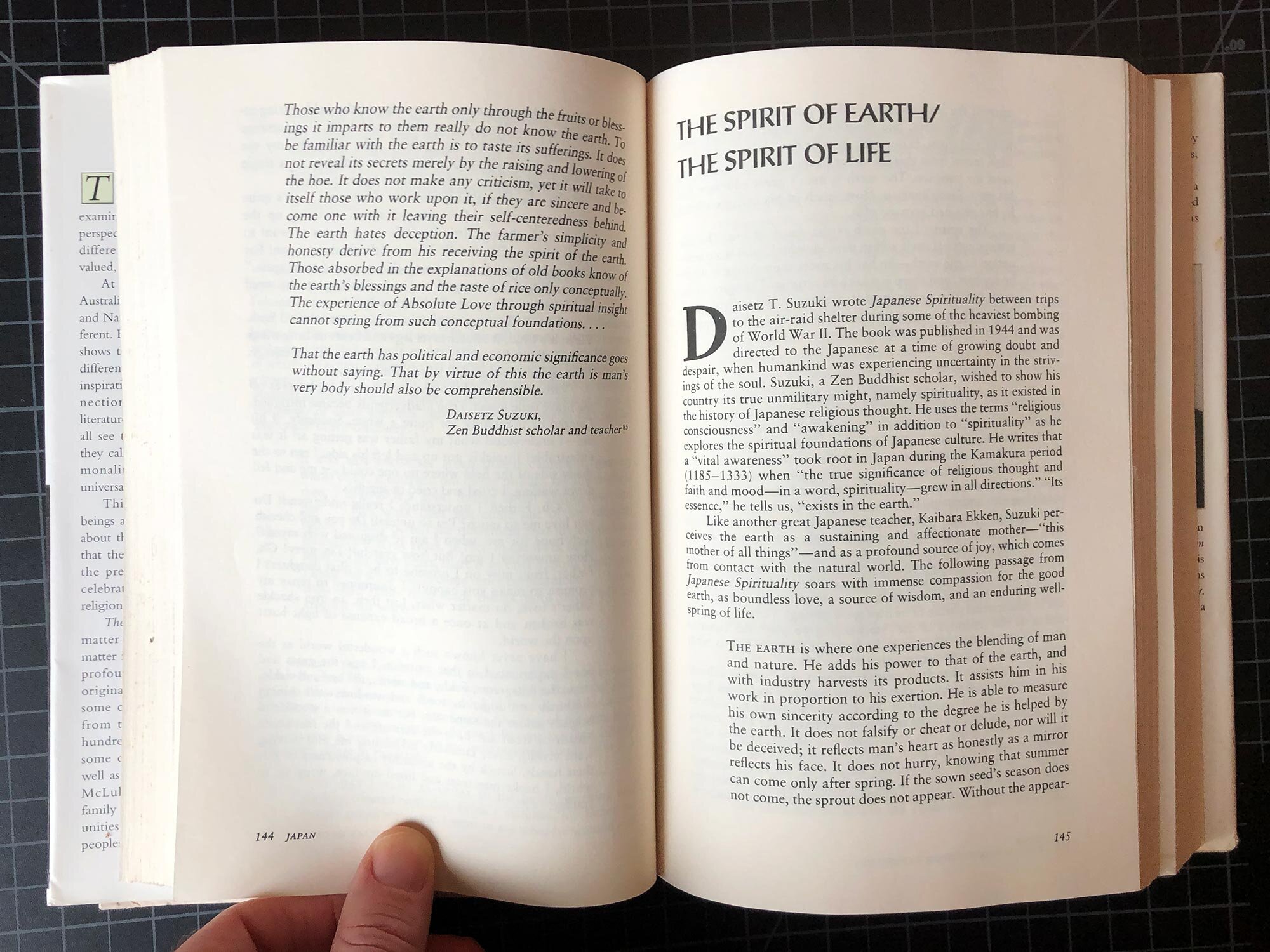

The Way of the Earth, a 1994 book by T.C. McLuhan, is full of stories, philosophy, poetry, and thoughts on nature and art. Subtitled “Encounters with nature in ancient and contemporary thought,” this is one of those books that you can flip open to any page and find something interesting.

There are also a few great passages on pottery pulled from Bernard Leach’s 1975 book Hamada, Potter.

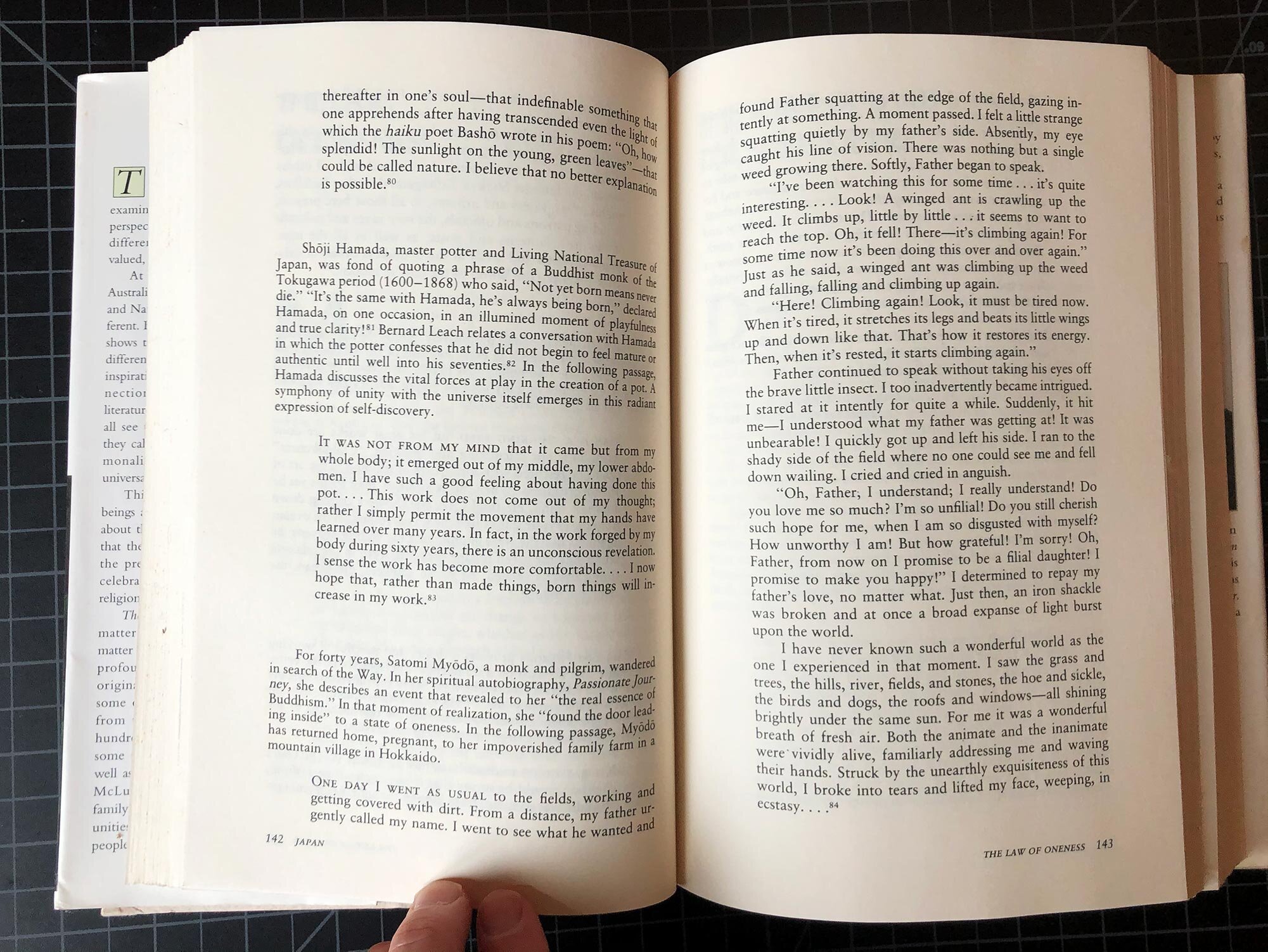

Here’s a passage from page 142:

Bernard Leach relates a conversation with Hamada in which the potter confesses that he did not begin to feel mature or authentic until well into his seventies. In the following passage, Hamada discusses the vital force at play in the creation of a pot.

It was not from my mind that it came but from my whole body; it emerged out of my middle, my lower abdomen. I have such a good feeling about having done this pot. . . This work does not come out of my thought; rather I simply permit the movement that my hands have learned over many years. In fact, in the work forged by my body during sixty years, there is an unconscious revelation. I sense the work has become more comfortable. . . I now hope that, rather than made things, born things will increase in my work.

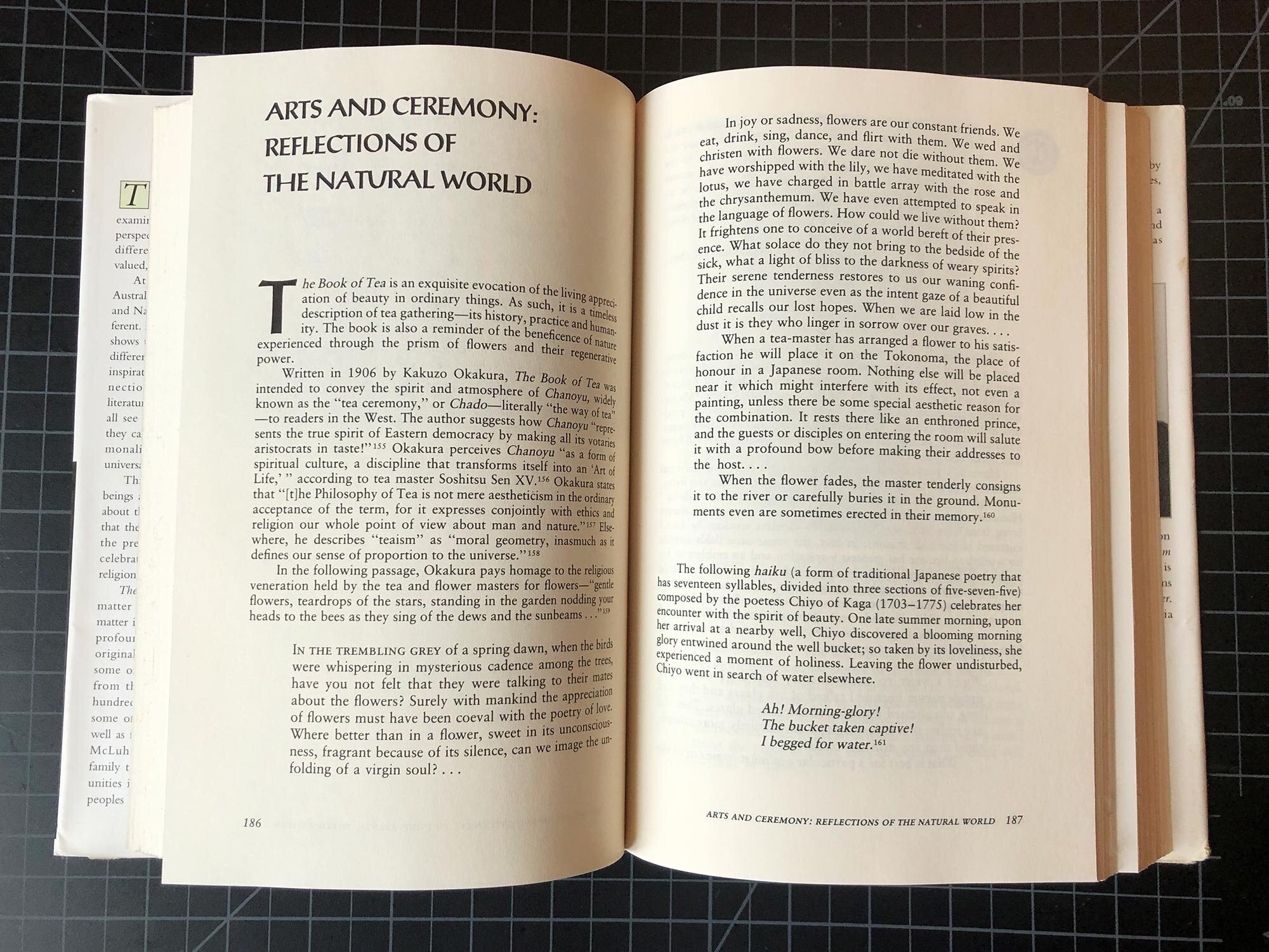

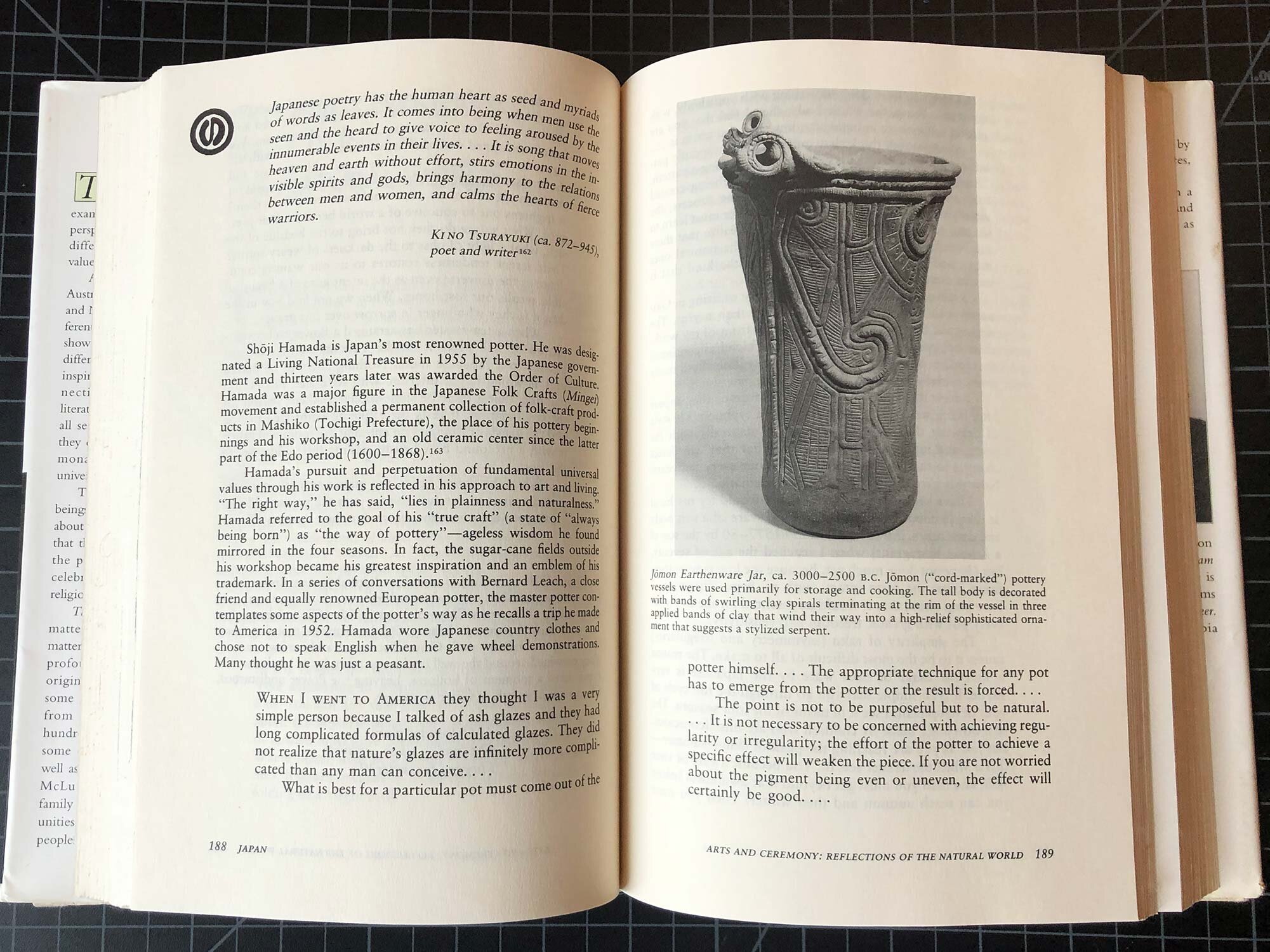

Later in the book, there’s a few pages devoted to Hamada. From page 188:

Shoji Hamada is Japan’s most renowned potter…Hamada was a major figure in the Japanese Folk Crafts (Mingei) movement and established a permanent collection of folk-craft products in Mashiko (Tochigi Prefecture), the place of his pottery beginnings and his workshop…Hamada’s pursuit and perpetuation of fundamental universal values through his work is reflected in his approach to art and living. “The right way,” he has said, “lies in plainness and naturalness.” Hamada referred to the goal of his “true craft” (a state of “always being born”) as “the way of pottery”—ageless wisdom he found mirrored in the four seasons. In fact, the sugarcane fields outside his workshop became his greatest inspiration and an emblem of his trademark. In a series of conversations with Bernard Leach, a close friend and equally renowned European potter, the master potter contemplates some aspects of the potter’s way as he recalls a trip he made to America in 1952. Hamada wore Japanese country clothes and chose not to speak English when he have wheel demonstrations. Many thought he was just a peasant.

When I went to America they thought I was a very simple person because I talked of ash glazes and they had long complicated formulas of calculated glazes. They did not realize that nature’s glazes are infinitely more complicated than any man can conceive. . .

What is best for a particular pot must come out of the potter himself. . . The appropriate technique for any pot has to emerge from the potter or the result is forced. . . The point is not to be purposeful but to be natural. . . It is not necessary to be concerned with achieving regularity or irregularity; the effort of the potter to achieve a specific effect will weaken the piece. If you are not worried about the pigment being even or uneven, the effect will certainly be good.

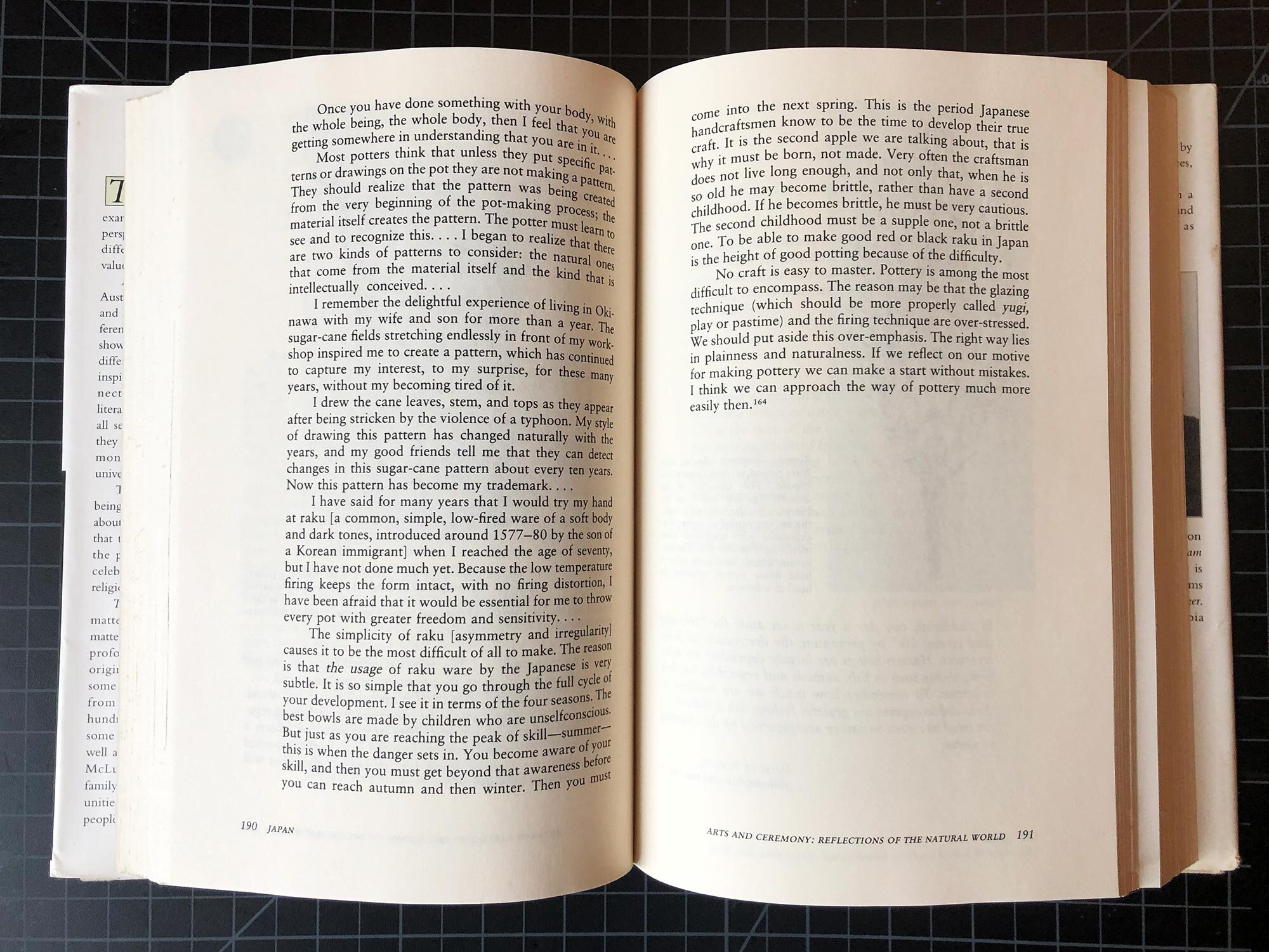

Once you have done something with your body, with the whole being, the whole body, then I feel that you are getting somewhere in understanding that you are in it. . .

Most potters think that unless they put specific patterns or drawings on the pot they are not making a pattern. They should realize that the pattern was being created from the very beginning of the pot-making process; the material itself creates the pattern. The potter must learn to see and to recognize this. . . I began to realize that there are two kinds of patterns to consider: the natural ones that come from the material itself and the kind that is intellectually conceived. . .

I remember the delightful experience of living in Okinawa with my wife and son for more than a year. The sugar-cane fields stretching endlessly in front of my workshop inspired me to create a pattern, which has continued to capture my interest, to my surprise, for these many years, without my becoming tired of it.

I drew the cane leaves, stem, and tops as they appear after being stricken by the violence of the typhoon. My style of drawing this pattern has changed naturally with the years, and my good friends tell me that they can detect changes in this sugar-cane pattern about every ten years. Now this pattern has become my trademark.

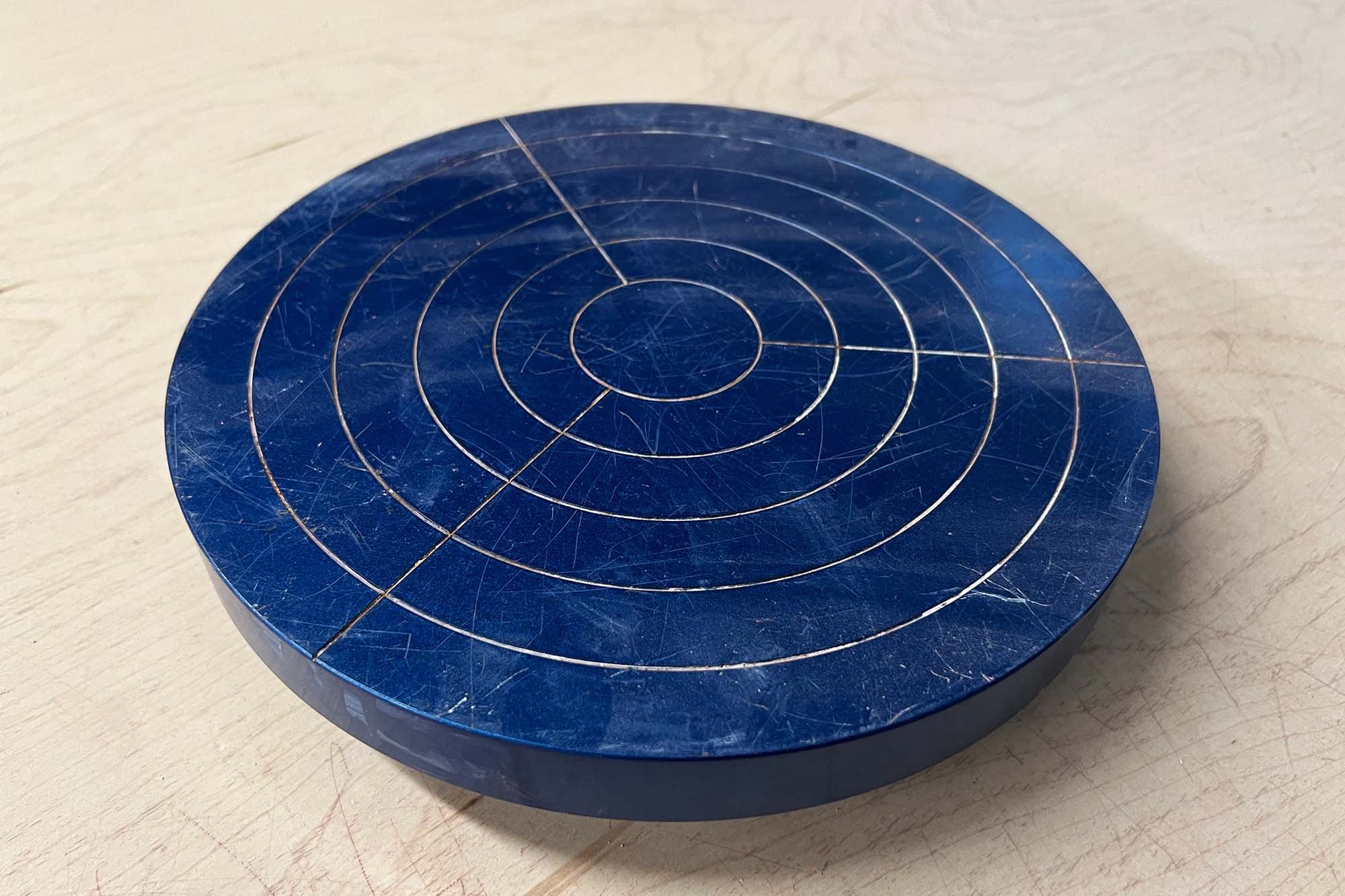

I have said for many years that I would try my hand at raku when I reached the age of seventy, but I have not done much yet. Because the low temperature firing keeps the form intact, with no firing distortion, I have been afraid that it would be essential for me to throw every pot with greater freedom and sensitivity. . .

The simplicity of raku [asymmetry and iregularity] cause it to be the most difficult of all to make. The reason is that the usage of raku ware by the Japanese is very subtle. It is so simple that you go through the full cycle of your development. I see it in terms of the four seasons. The best bowls are made by children who are unselfconscious. But just as you are reaching the peak of skill—summer—this is when the danger sets in. You become aware of your skill, and then you must get beyond that awareness before you can reach autumn and winter. Then you must come into the next spring. This is the period Japanese handcraftsmen know to be the time to develop their true craft. It is the second apple we are talking about, that is why it must be born, not made. Very often the craftsman does not live long enough, and not only that, when he is so old he may become brittle, rather than have a second childhood. If he becomes brittle, he must be very cautious. The second childhood must be the supple one, not a brittle one. To be able to make a good red or black raku in Japan is the heigh of good potting because of the difficulty.

No craft is easy to master. Pottery is among the most difficult to encompass. The reason may be that the glazing technique (which should be more properly called yugi, play or pastime) and the firing technique are over-stressed. We should put aside this over-emphasis. The right way lies in plainness and naturalness. If we reflect on our motive for making pottery we can make a start without mistakes. I think we can approach the way of pottery much more easily then.

For more on Shoji Hamada, check out Hamada Potter, by Bernard Leach. (Shop at Amazon | Shop at Abebooks)

For more essays like this, find a used copy of The Way of the Earth by T.C. McLuhan (Shop at Amazon | Shop at Abebooks)

Flip through the pages cited in this post:

For more posts on books, podcasts, and studio inspiration, click here.