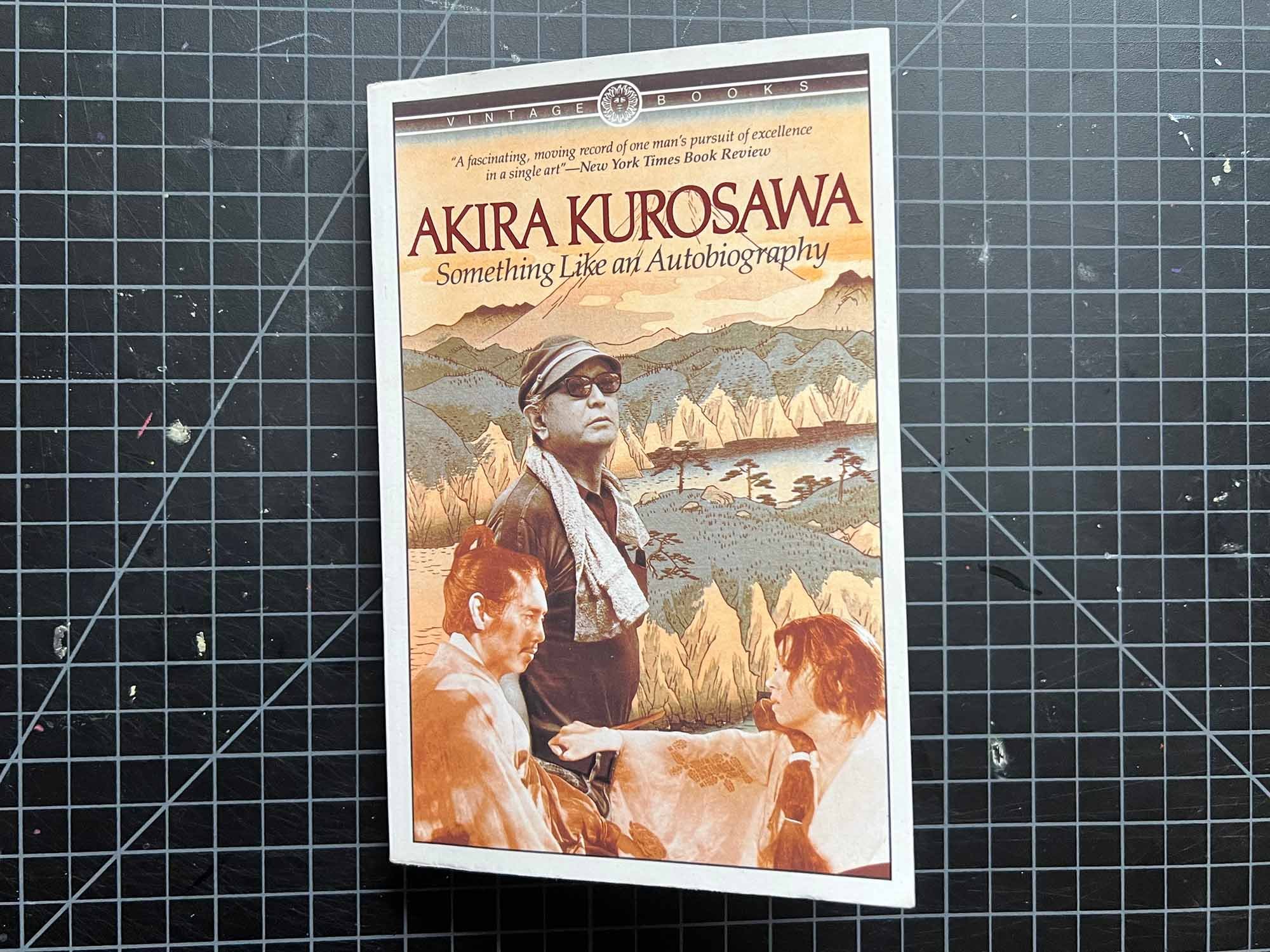

Akira Kurosawa’s 1982 book, Something Like an Autobiography, is a great read, detailing the childhood of the famous Japanese film director and his and early years in the film industry, up to his breakout film, Rashomon.

In the chapter Negative and Positive, Kurosawa addresses the suicide of his beloved older brother and how that led him to abandon painting and enter the film industry.

Negative and Positive

What if…” I still wonder sometimes. If my brother had not committed suicide, would he have entered the film world as I have done? He had a great knowledge of the films and more than enough talent to understand filmmaking, and he had many appreciative friends in the film world. He was still young, so I’m sure he could have made a name for himself if he had wanted to.

But probably no one could have changed my brother’s mind once it was made up. He was overwhelmed by that first defeat when as a superior student he failed the entrance examination for the First Middle School. At that point he developed a wise but pessimistic philosophy of life that saw all human effort as vanity, a dance upon the grave. When he encountered the hero expounding this philosophy in The Last Line, he probably clung all the more steadfastly to it. Moreover, my brother, so fastidious in all things, was not the sort of person to be wishy-washy about any statement he had once made. He must have seen himself as already sullied by worldly affairs and on his way to becoming the kind of ugly person he despised.

In later years when I was chief assistant director on Yamamoto Kajiro’s film, Tsuzurikata kyōshitsu (Composition Class, 1938), the lead was being played by Tokugawa Musei, the famous silent-film narrator. One day he looked at me with a long, curious stare and said, “You’re just like your brother. But he was negative and you’re positive.” I thought it was a matter of my brother having preceded me in life, and that is how I understood Musei’s comment. But he went on to say that our appearance was exactly the same, but that my brother had had a kind of dark shadow in his facial expression and that his personality, too, had seemed clouded. Musei felt that my personality and face were, by contrast, sunny and cheerful.

Uekusa Keinosuke has also said my personality is like that of a sunflower, so there must be some truth to the allegation that I am more sanguine than my brother was. But I prefer to think of my brother as a negative strip of film that led to my own development as a positive image.

I was twenty-three years old when my brother died. I was twenty-six when I entered the film world. During the three-year interval nothing very noteworthy occurred in my life. The only major event had taken place before my brother’s suicide. This was the news that my oldest brother, who had not been heard from for a long time, had died of an illness. The deaths of my two older brothers left me the only son, and I began to feel a sense of responsibility toward my parents. I became impatient with my own aimlessness.

But in those days it was much harder than it is now to succeed as an artist. And I had begun to have doubts about my own talent as a painter. After looking at monographs on Cézanne, I would step outside and the houses, streets and trees—everything—looked like a Cézanne painting. The same thing would happen when I looked at a book of Van Gogh’s paintings or Utrillo’s paintings—they changed the way the real world looked to me. It seemed completely different from the world I usually saw with my own eyes. In other words, I did not—and still don’t—have a completely personal, distinctive, way of looking at things.

This discovery did not surprise me unduly. To develop a personal vision isn’t easy. But when I was a young man, this insufficiency caused me not only dissatisfaction but uneasiness. I felt like I had to fashion my own way of seeing, and I became more impatient. Every exhibition I went to seemed to prove to me that every painter in Japan had his own personal style and his own personal vision. I became more and more irritated with myself.

As I look back on the art scene, it’s clear to me that very few of the painters whose work I saw really had a personal style and vision. Most of them were just showing off with a lot of forced techniques, and the result was mere eccentricity. I don’t recall who wrote it, but there was a song about someone who is unable to state outright that what is red is red; the years go by, and it is not until his old age that he finally becomes certain. And that’s just how it is. During youth the desire for self-expression is so overpowering that most people end up by losing all grasp on their real selves. I was no exception. I strained to perform technical tours de force as I painted, and the resulting pictures revealed my distaste for myself. Gradually I lost confidence in my abilities, and the act of painting itself became painful for me.

What is worse, I had to do boring outside work in order to earn the money to buy my canvases and paints. It consisted of things like illustrations for magazines, visual teaching aids for cooking schools on the correct way to cut giant radishes, and cartoons for baseball magazines. The result of spending my time on a kind of painting for which I felt no enthusiasm at all was a further, more irrevocable loss of my real desire to paint.

I began to think about going into some other profession. Deep down inside I really felt that anything at all would do; all I was concerned about was putting my mother’s and father’s minds at ease. This feeling of casting about was intensified by my brother’s sudden death. Since I had been doing nothing but follow my brother’s lead, his suicide sent me spinning like a top. I believe this was a very dangerous turning point in my life.

Through all of this my father did not let me loose to spin on my own. He just kept telling me as I became more and more panicky, “Don’t panic. There’s nothing to get excited about.” He told me that if I would just wait calmly, my road in life would open up to me of its own accord. I don’t know exactly what kind of viewpoint led him to tell me such things; perhaps he was speaking from his own experience of life. As it turned out, his words proved amazingly accurate.

One day in 1935, as I was reading the newspaper, a classified advertisement caught my eye. The P.C.L. (always called that, though the full name was Photo Chemistry Laboratory) film studios were hiring assistant directors. Up until that moment it had never occurred to me to enter the film industry, but when I saw that advertisement, my interest was suddenly aroused. The ad said that the first test for prospective employees would be a written composition. The theme of this essay was to be on the fundamental deficiencies of Japanese films. One was to give examples and suggest ways to correct the problems.

This struck me as very interesting. From this test question I got a sense of the youthful vigor of the newly established P.C.L. company. The theme of fundamental deficiencies and the ways to overcome them gave me something I could sink my teeth into, and at the same time it appealed to my perverseness and sense of mischief. If the deficiencies were fundamental, there was no way to correct them. So I began writing in half-mocking spirit.

I don’t remember the precise contents of my essay but I had thoroughly savored and consumed foreign films under my brother’s tutelage, and as a movie fan I found many things in Japanese cinema that did not satisfy me. I undoubtedly gave vent to all my accumulated criticism and had a fine time doing so. Along with the test essay an applicant for the assistant director’s job was to submit a curriculum vitae and a copy of the family register setting forth his antecedents. Since I was prepared to take any job that came along, I already had copies of my curriculum vitae and family register waiting in my desk drawer. I dispatched them with my essay to P.C.L.

A few months later I received notification of the second round of testing. I was told to appear at the P.C.L. studios on a certain day at a certain time. Feeling as if I had been bewitched by a fox to have written that kind of essay and have it accepted, I proceeded as ordered to the P.C.L. studios.

I had once seen a photograph of the P.C.L. studios in a film magazine. It showed a white building with palm trees in front of it, so I had thought it must be located along the beach in Chiba Prefecture, many miles from Tokyo. It turned out to be in a southwestern suburb of the city, a very prosaic place. How little I knew of the realities of the Japanese film industry, and how little I dreamed of ever working it it! But I found my way to the P.C.L. studios, and there I met the best teacher of my entire life, “Yama-san”—the film director Yamamoto Kajirō.

— Akira Kurosawa

Something Like an Autobiography

by Akira Kurosawa

translated by Audie E. Bock

198 pages, 1982, Vintage Books

This excerpt made me think of Crows, a scene about Van Gogh from the 1990 film, Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams.