The Slip is a 2023 book by Prudence Peiffer that tells the story of art studios on Coenties Slip in New York City in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Slip, located at the very southern tip of Manhattan, was an in-between area that had been full of shipyards and sail-making factories, but was about to become the skyscraper financial district we know today. For almost a decade, artists filled many of the spaces, making work, community, and finding new paths forward for American art. It’s a fascinating, wonderful book that weaves together so much, including the stories of Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Indiana, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, and Lenore Tawney.

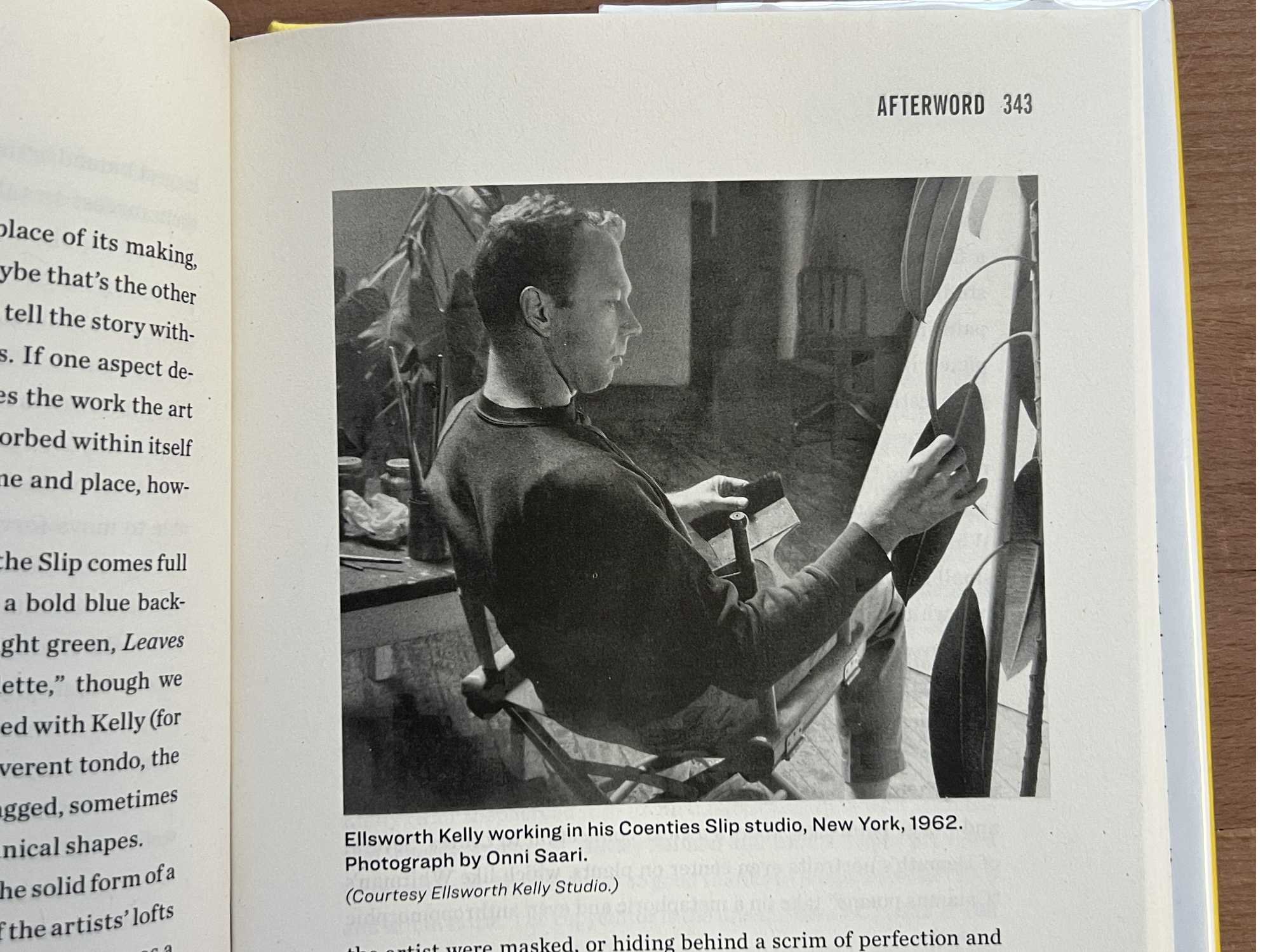

The following excerpt details Ellsworth Kelly’s fascination with drawing plants.

Plants in the foreground of Ellsworth Kelly’s studio in 1961

Kelly was always planting pits or seeds—he grew avocado, orange, grapefruit, and lemon trees this way. Everyone at the Slip had avocado plants, as they were easy to grow from pits. (A 1951 article in The New York Times) explained exactly how to cultivate these exotic fruites with toothpicks, a glass, and water.) Robert Indiana filled the old elevator shaft in his loft with pots of them, ferns, and fir tree saplings, reflecting his own interest in plants. (His favorite course in Edinburgh had been botany, held in the queen’s botanical gardens.) He also hung found wheels, metal chains, winches, and stencils from the building’s previous occupants, Marine Works ship suppliers. He drew from the avocado plants that “flourish under the skylights of the Marine Works,” as he wrote in his autochronology for the year 1957. Even Daphne Seyrig wrote to her parents in Beirut with instructions on exactly how to grow avocados, and though she hated their taste, she gave a recipe for a trendy new dish that was very easy to prepare and a little like hummus. It was called guacamole.

For Kelly, the plants were more than cheap decor. He made sure he had plenty because he wanted to draw them. They were an “already-made” subject matter of endless variety. Later he would say that he chose them because “I knew I could draw plants forever.” His studio would soon be filled with sketches of plants. They breathed oxygen into his paintings too.

Plants in the background of this 1958 image of Ellsworth Kelly in his studio.

His very first plant drawing was a daffodil on the cover of his junior high school journal, Chirp, in April 1938. In damp February 1949 in Paris, Kelly had bought a little hyacinth plant at the flower market and brought it back to his small, cold room at the Hôtel de Bourgogne to “cheer myself up”; its bright perfume soon filled the air. He began to draw the flower, which was the start of a series of delicate contour line drawings of plants that he would make wherever he was living: fig leaf, seaweed, artichoke, wild grape, burdock.

Kelly’s plant drawings evoked the confident, spare lines of two artists most important to him: Matisse and Calder. But they had their own, independent essence; Kelly called them “portraits.” When he first began making them in Paris, he was also drawing his friends—fast sketches in pencil at cafés, on park benches. Friends were ready-made models, but Kelly’s incessant sketching was also a declartion that these composers, writers, dancers from Merce Cunningham’s company, would make it someday and these portraits would be part of that story. He felt the need to be drawing endlessly, as if there were a direct line between his eyes and hands.

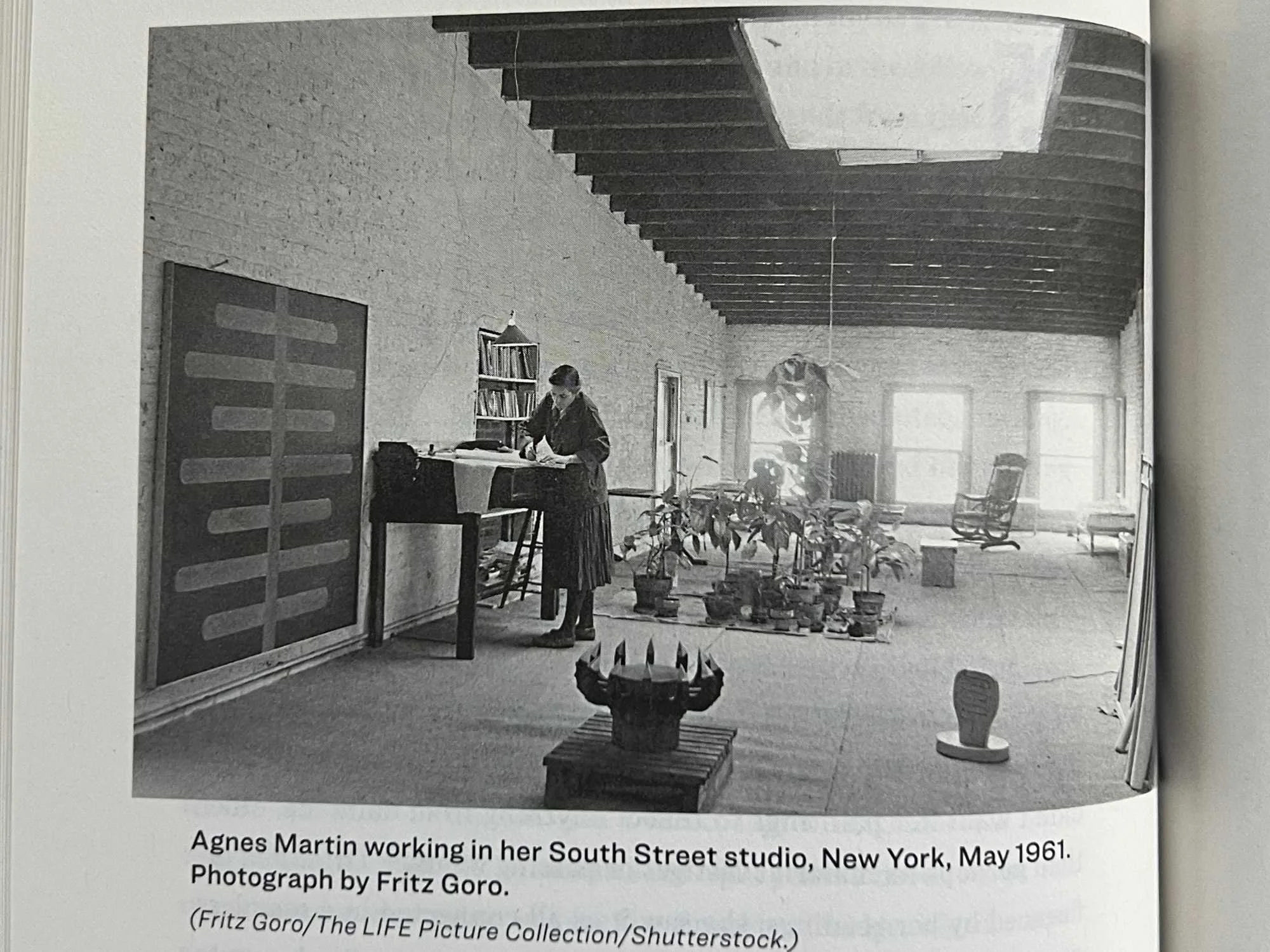

Plants in the midground of this 1961 image of Agnes Martin working in her Coenties Slip studio.

In 1957, the plant drawings became a kind of daily practice at the Slip: when he first got up, or when he needed a break from painting. They were quick, instinctual, mostly made in ink or pencil; he never erased a line as he was working on them, and he discarded a lot.

…

It’s not just that nature provided subjects for Kelly that were “already-made.” or that his drawings allowed him to think through forms in a way that instructed all of his paintings. He saw nature itself as the ultimate artist. “I want to work like nature works,” Kelly said, as if channeling the poet John Keats. “I want to paint in a way that trees grow, leaves come out—how things happen.” That he internalized the process of nature’s spontaneous creation in producing a thing of beauty in itself helps us see how a continous project that might otherwise be dismissed as a hobby could be at the cneter of his art. He called his plant drawings “the point of departure for all of my later work.” This was about figuring out form—the curve or overlapping shpaes of leaves. And about a direct trasnfer of what is seen. “I didn’t solve the painting by doing it; I sovle it before with drawings.” Nature, for Kelly, was not just the world apart from human intervention—it was everything around him that was unaltered, giving his vision a kind of ecology that encompassed the whole environment. The city, then, could be as much a source of nature as a field or an ocean; it, too, is an ecological site. Nature is entwined with place in Kelly’s view. And the persistence of place undergirds every abstraction he ever made. When asked, as an atheist, if there was anything he believe in, he answered without pause, “nature.”

The cover of The Slip by Prudence Peiffer.

The Slip: The New York City Street That Changed American Art Forever

By Prudence Peiffer

411 pages, published by Harper Collins, 2023

Shop the book new and used at the following links: