Daybook by Anne Truitt, the 1984 Penguin paperback edition.

This text is from Anne Truitt’s journal Daybook. First published in 1982, it’s been in print since and is a wonderful book that should be on every artist’s bookshelf. Truitt was known for her minimalist sculptures and paintings. She also published three journals, including Daybook, Turn, and Prospect, that chronicled her approaches to art making, parenthood, memories, and thoughts on life as an artist.

This journal entry is from 1975, but is reflecting on 1961, about a year after the birth of Truitt’s son. In this passage, she describes how she started making the work that became her signature style.

From Daybook, by Anne Truitt:

27 March, 1975

It was in this familiar context that, one year after Sam’s birth, my work suddenly erupted into certainty. I was taken by surprise and to this day do not know why it happened.

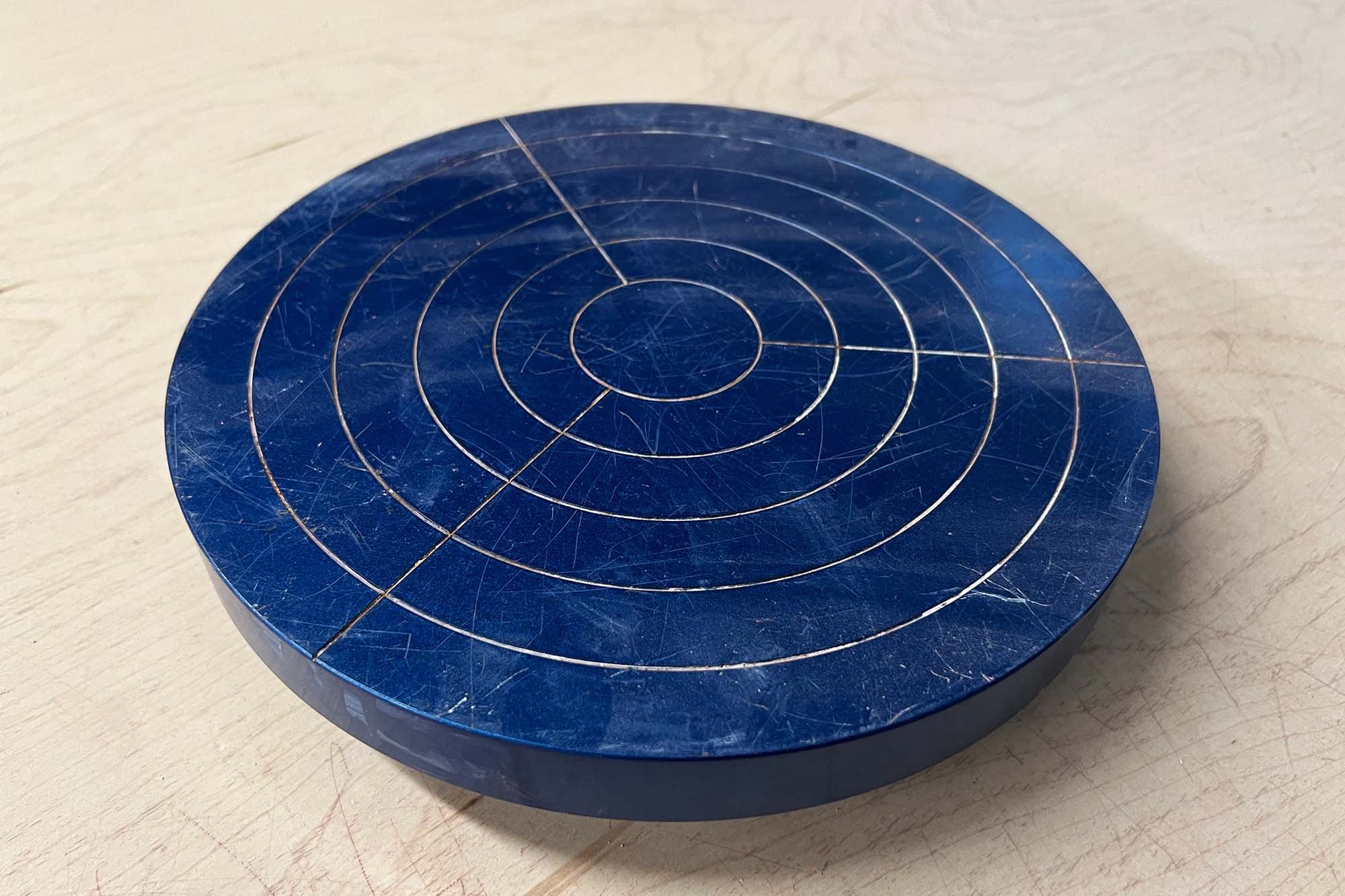

When Sam was a few months old, fairly launched, I rented a room at 1506 30th Street, across from our house. On the third floor, looking west from a sort of turret that jutted out into the air, it was rather pokey but exceedingly convenient as I could run back and forth easily. I picked up my work where I had left off in San Francisco and continued to make loose drawings with black and brown ink. These were done very fast, on sheets of newsprint paper into which the ink was absorbed in such a way as to make them look more expressionistic than they were in my mind. I was on the track of square and rectangular shapes, articulated back into the depth of the ink, echoing the structures I had seen on archeological sites in Mexico, most particularly those of Mayan temples. I began making these obsessively repetitive shapes in the summer of 1958 after Mary’s birth, not only in drawings but also in three dimensions. I used very dark brown clay, heavily grogged, and built up the sculptures from the inside out, using the classical method taught me by Alexander Giampietro. I still sometimes miss the marvelous feeling of rolling the clay between my fingers and thumb and then pushing the warm, full shape against its fellows to swell the unity of a structure growing slowly under my hand. This satisfaction with the certainty of a familiar and compatible process was one of the pleasures I had to forego when my work changed direction and forced me to go against the grain of my own taste and training.

On a visit to my studio early in 1961, Kenneth Noland pointed out to me the possibility of enlarging the scale of these sculptures. I remember my reluctance to absorb this idea, partly because I was afraid and partly because of my pleasure in using clay in a way that gave me such satisfaction. I think, however, that his suggestion opened up my thinking and combined with my obsessive concern with the weights of squares and rectangles to pave the way for the change that took place some months later.

The change itself was set off by a weekend trip to New York with my friend, Mary Pinchot Meyer, in November 1961, almost one year to the day after Sam’s birth. We went up on Saturday and spent the afternoon looking at art. This was my first concentrated exposure since 1957, when I had moved to San Francico, and I was astonished to note the freedom with which materials of various sorts were being used. More specifically, how they were being put to use. That is, I noticed that the materials were used without particular attention to their intrinsic bent, as if what I had always thought of as their natural characteristics was being disregarded. For the first time, I grasped the fact that art could spring from concept, and medium could be in its service. I had always rooted myself in process, the thrust of my endeavor being to seek patiently and unremittingly how an idea would emerge from a material. My insight into the art I saw that afternoon reversed this emphasis, throwing the balance of meaning from material to idea. And this reversal released me from the limitations of material into the exhilarating arena of my own spirit.

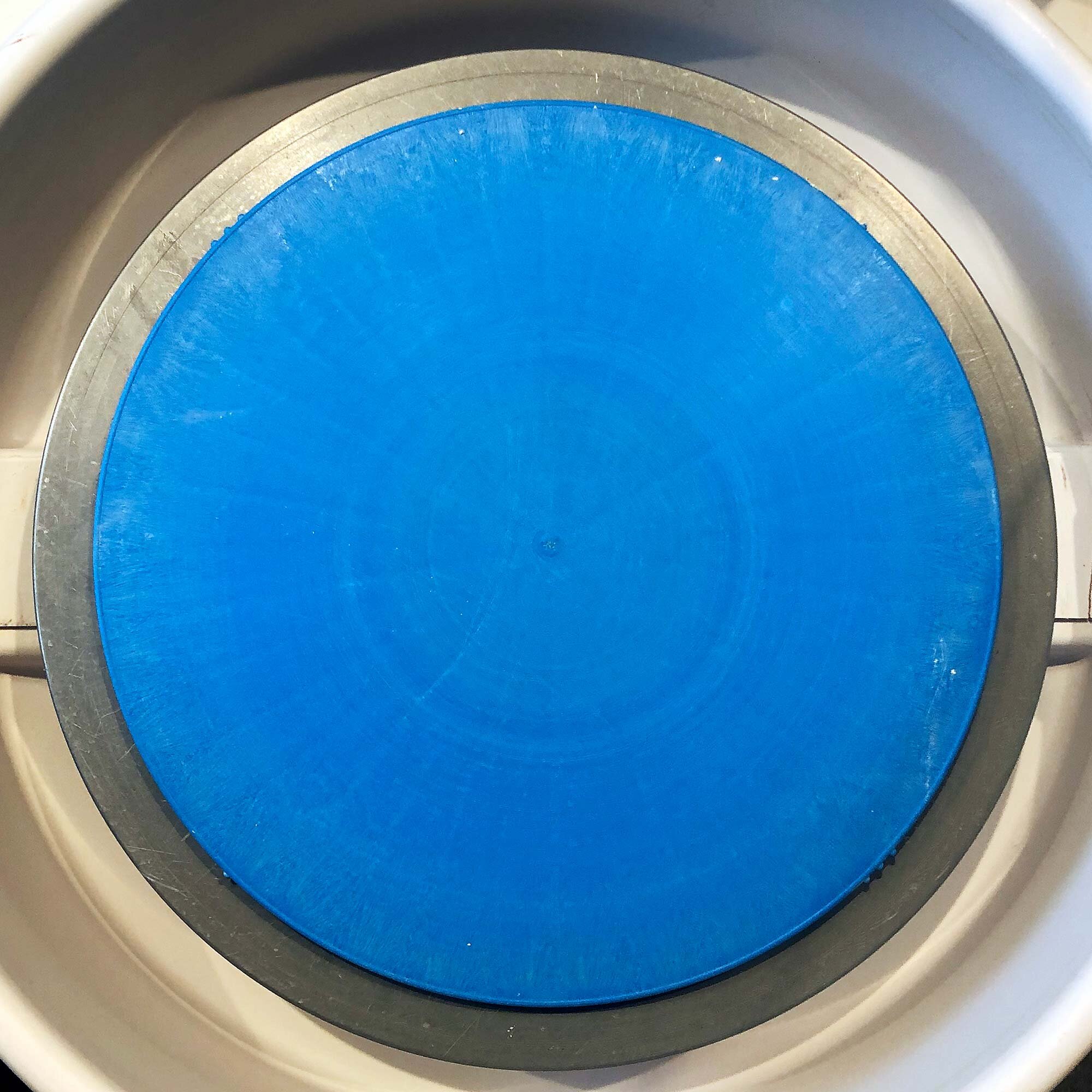

At the Guggenheim Museum, I saw my first Ad Reinhardt. I was baffled by what looked to be an all-black painting and enchanted when Mary pointed out the delicate changes in hue. I remember feeling a wave of gratitude—to her for showing me such an incredibly beautiful fact and to the painter for having made it to be seen. Farther along the museum’s ramp, a painting constructed with wooden sticks and planes also caught my attention, setting off a kind of home feeling; I do not remember the artist’s name but liked his using plain old wood such as I had seen all my life in carpentry. And when we rounded into the lowest semicircular gallery, I saw my first Barnett Newman, a universe of blue paint by which I was immediately ravished. My whole self was lifted into it. “Enough” was my radiant feeling—for once in my life enough space, enough color. It seemed to me that I had never before been free. Even running in a field had not given me the same airy beatitude. I would not have believed it possible had I not seen it with my own eyes. Such openness wiped out with one swoop all of my puny ideas. I staggered out into the street, intoxicated with freedom, lifted into a realm I had not dreamed could be caught into existence. I was completely taken by surprise, the more so as I had only earlier that day been thinking how I felt like a plowed field, my children all born, my life laid out; I saw myself stretched like brown earth in furrows, open to the sky, well planted, my life as a human being complete. My yearning for a family, my husband and my children, had been satisfied. I had looked for no more in the human sense and felt content.

I went home early to Mary’s mother’s apartment, where we were staying, thinking I would sleep and absorb in self-forgetfulness the fullness of the day. Instead, I stayed up almost the whole night, sitting wakeful in the middle of my bed like a frog on a lily pad. Even three baths spaced through the night failed to still my mind, and at some time during these long hours I decided, hugging myself with determined delight, to make exactly what I wanted to make. The tip of balance from the physical to the conceptual in art had set me to thinking about my life in a whole new way. What did I know, I asked myself. What did I love? What was it that meant the very most to me inside my very own self? The fields and trees and fences and boards and lattices of my childhood rushed across my inner eye as if borne by a great, strong wind. I saw them all, detail and panorama, and my feeling for them welled up to sweep me into the knowledge that I could make them. I knew that that was exactly what I was going to do and how I was going to do it.

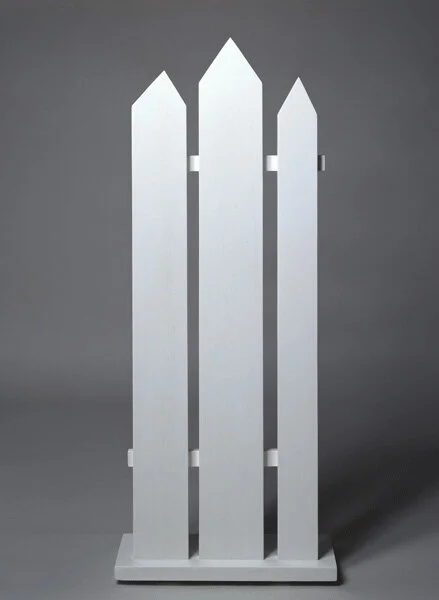

Anne Truitt, First, 1961. Acrylic on wood, 44 1/4 x 17 3/4 x 7 inches. Image via annetruitt.org.

Mary Meyer and I returned to Washington the next day, and early Monday morning I bought some white shelf paper and went to my studio. There I drew to full size three 54” irregularly pointed boards, backed by two rectangular boards, placed on a flat rectangular board. I went straight down 30th Street to a lumber store and ordered the boards cut to the size of my drawing; I bought clamps and glue and some white house paint. When the boards were ready, I glued them together, painted them, and there was my sculpture: First.

I returned immediately to the lumber store with two more drawings. While I was explaining to the man what I wanted and what I intended to do, he said mildly, “You can have them put together across the street if you want to, in our mill.” “Oh, can I?” I said. “Thank you.” And I seized my daughter Mary in her dark blue snowsuit from the counter where she had been perched to watch what was going on. I had to rush off for a carpool and hadn’t time to go to the mill right then, but I remember stopping outside the store and going down on my knees in the snow to hug Mary and tell here that I could make whatever I wanted to now, overcome by the possibilities that surged into my mind. I had seen that size would be a problem and had had no idea how I was going to make what I saw in my mind in that little studio with my meager equipment, time, and strength.

When I got back to the mill, I went in to see the manager. He placidly looked at my roll of drawings and allowed as how he could make them up for me. But, he suggested, I could make scale drawings and that would be easier for us both. So off I went and bought a scale ruler. A young architectural student was buying something at the same time and showed me how to use it. So I set up a system: scale drawings and mill fabrication. I also telephoned the financial advisor who had charge of the money I had inherited and asked him to transfer five thousand dollars into a new, special checking account. I used this account exclusively for my work from then on, replenishing the funds from my capital without giving it too much thought.

Anne Truitt, 1978.

In 1962, I made thirty seven sculptures, ranging in size from that of the first fence up to around ten feet tall. Most of these I made in Kenneth Noland’s studio in Twining Court, which he generously allowed me to rent for ten dollars a month after his departure for New York. It was a ramshackle old carriage house with a huge hayloft equipped with a large hay door and hooked lift, which I used to hoist the larger sculpture in and out. There were also four other rooms, two crammed with rusted bedsprings; I had these carted off, and then whitewashed one of the rooms so I had a place for finished work. No heat, no water, rats—I used to stamp my feet when I came in—and the place was dismally damp. No matter.

— Excerpt from Daybook by Anne Truitt, 1984 paperback edition, pages 148–153.